Jednym z najbardziej niezwykłych aut wyścigowych jest Monaco-Trossi. To… coś powstało w 1935 roku z inicjatywy i wedle pomyślunku Augusto Camillo Pietro Monaco. Miał chłop fantazję – trzeba mu przyznać. To nie był pierwszy jego pokurwiony projekt. Zdążył już do tej pory tchnąć życie w inne herezje, no ale nic nie mogło się równać z jego nowym pomysłem.

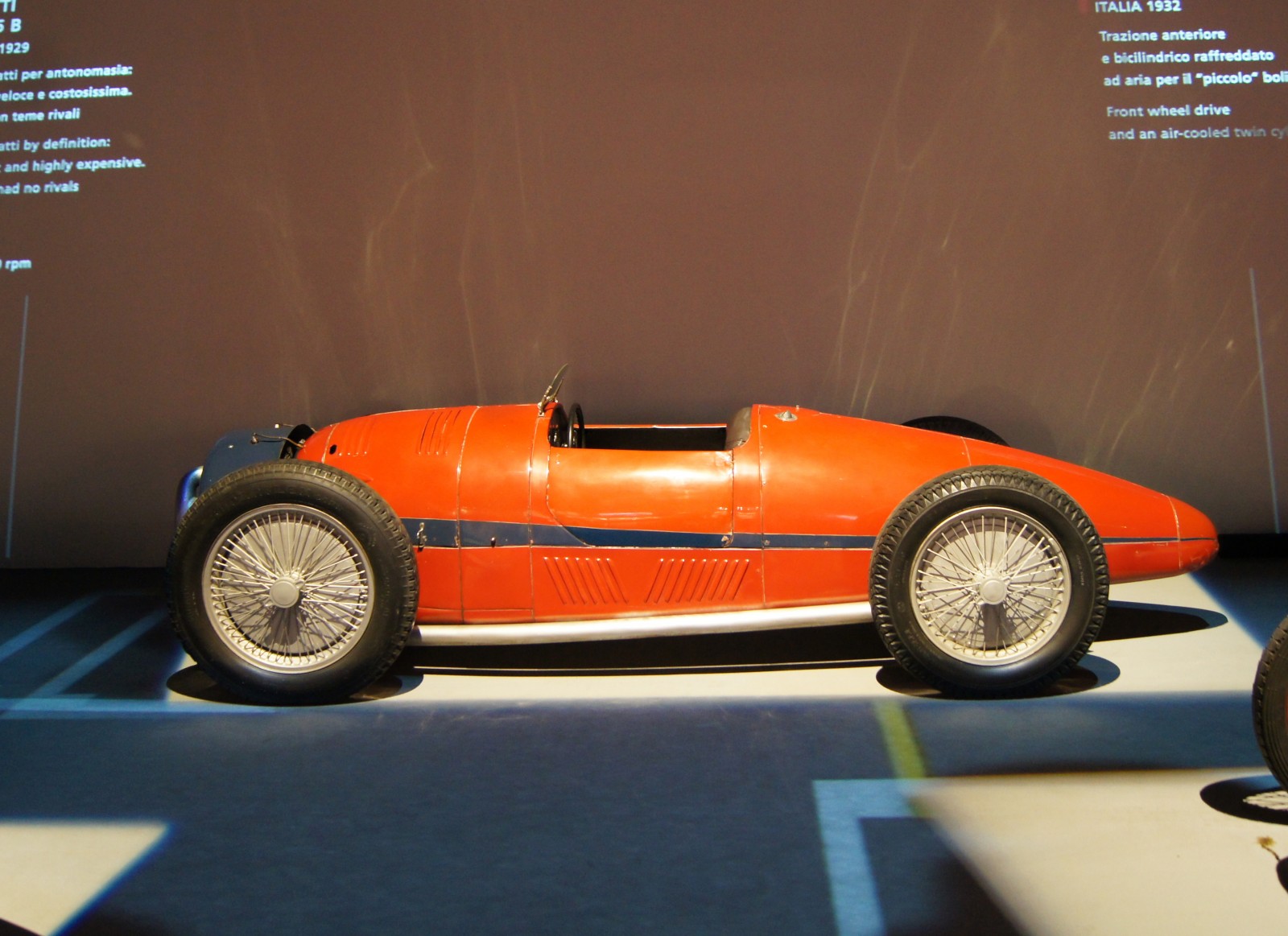

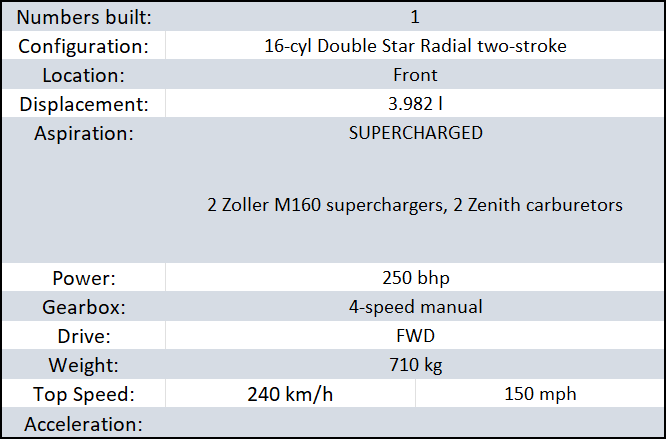

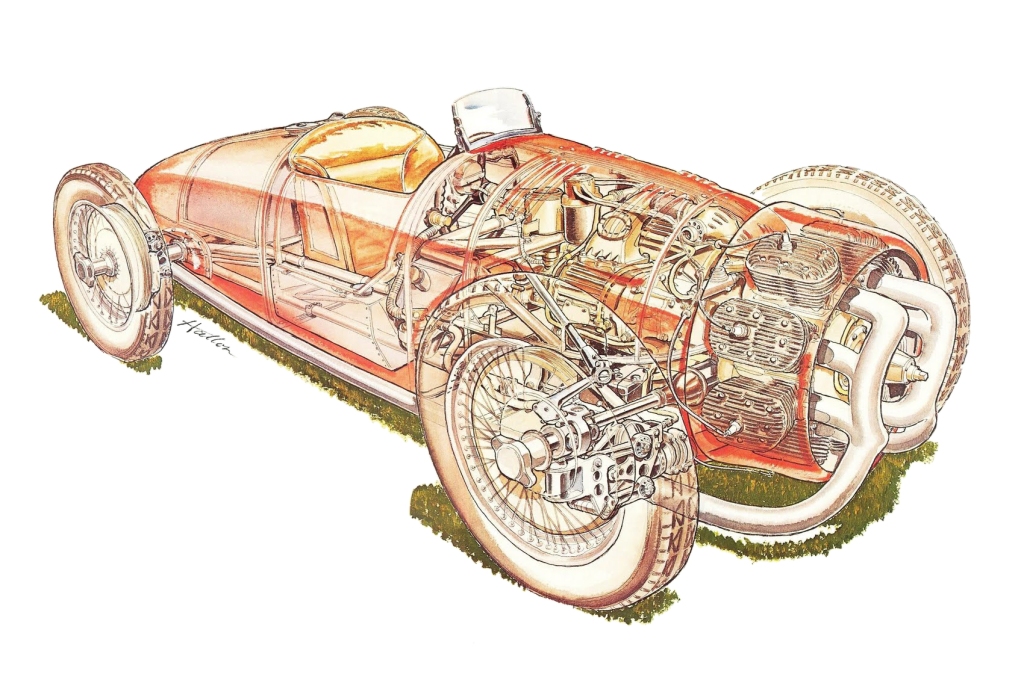

Ten pojazd jest ciekawy z dwóch powodów. Tym, który się rzuca w oczy jest 16-cylindrowy silnik w układzie gwiazdowym na przedzie. Jest to Double Star o pojemności 4 litrów. Dwusuw chłodzony powietrzem i gotów rozwijać 250 koni mechanicznych. Drugim interesującym punktem tego auta jest napęd przeprowadzony na przód. Nie żartuję – dokładnie tak się stało. Jest to unikat, jeśli chodzi o auta do Grand Prix. To było śmiałe podejście pod wieloma względami.

Pierwsze, co człowiekowi przychodzi do głowy – “dlaczego na przód? Przecież to jest upośledzenie w kontekście wyścigów – i to na własne życzenie”. No, tak – a o co chodzi? Monaco-Trossi ma pewne zalety. Jako, że silnik jest chłodzony powietrzem, to umieszczenie go jako wysunięty z przodu – sprzyja temu jak najbardziej. Po drugie silnik z przodu przyciska do asfaltu oś napędową, co powinno skutkować dodatkową trakcją. Są też jednak minusy… 16 cylindrów przed przednią osią skutkuje rozkładem mas 75-25, co oznacza dramatyczną podsterowność, a olbrzymi motor daje za duży docisk, przez co koła właśnie gubią trakcję zamiast jej dostarczać.

Jak w ogóle do tego doszło… Augusto Monaco był wbrew pozorom wprawnym inżynierem. Budował pojazdy, które nadawały się do Grand Prix i miał ambicję zbudowania auta, które mogłoby startować w klasie dla 750 kilogramów. Ze wsparciem Ayminiego, który oprócz ścigania się również był inżynierem, oraz ze strony FIATa, którego faktorii mógł używać do opracowania, jak i testów swojej maszyny – zbudował wtedy silnik: dwusuw w układzie gwiazdowym. Chora rzecz – ja wiem. Co chwila były z nim problemy i FIAT w końcu wycofał wsparcie, którego Monaco tak bardzo potrzebował.

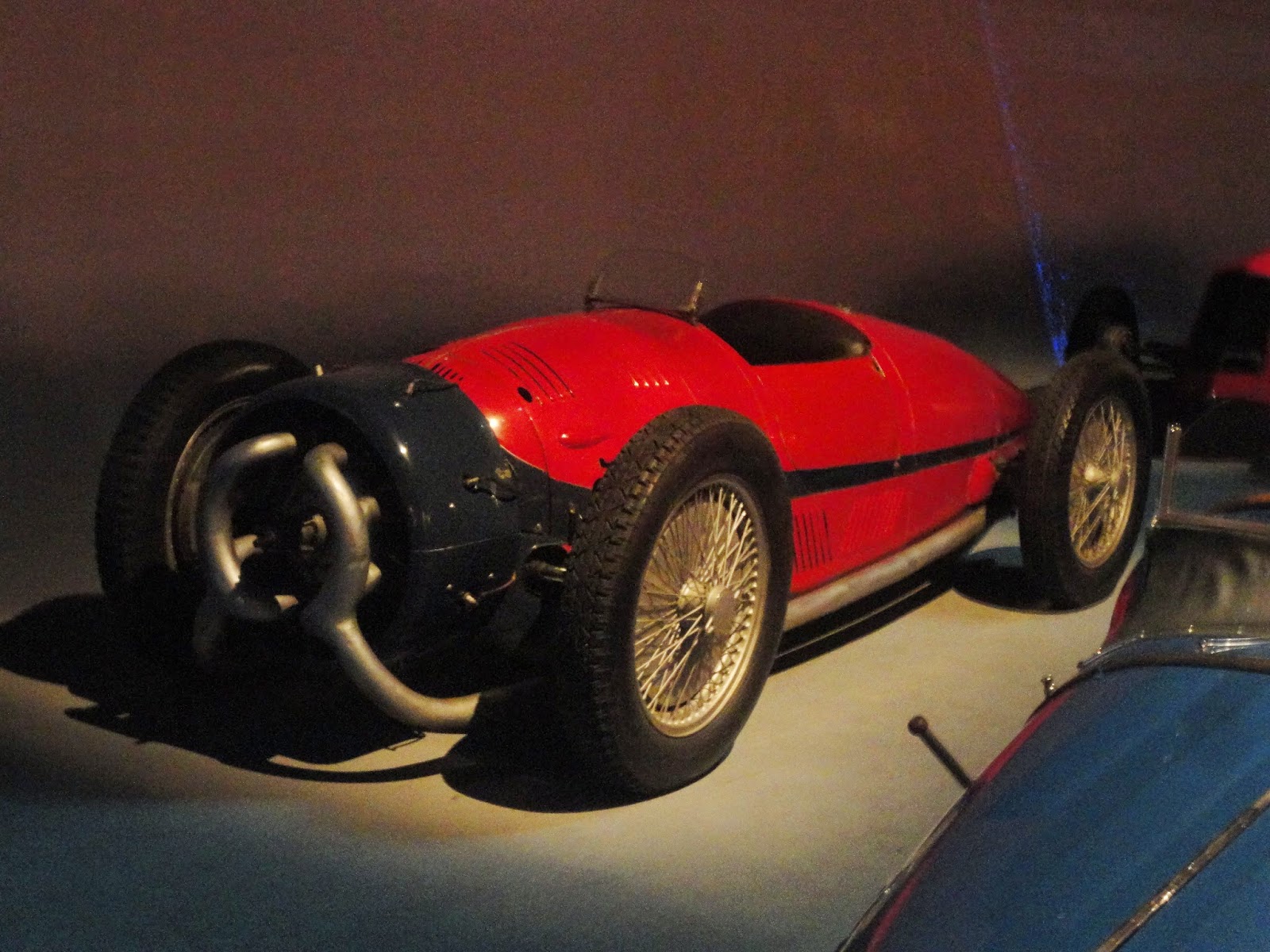

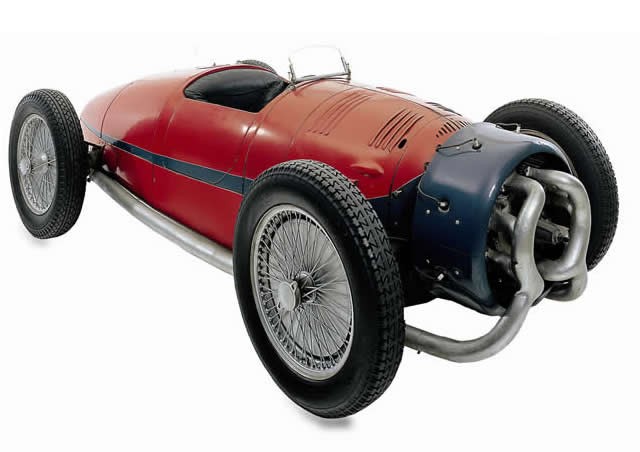

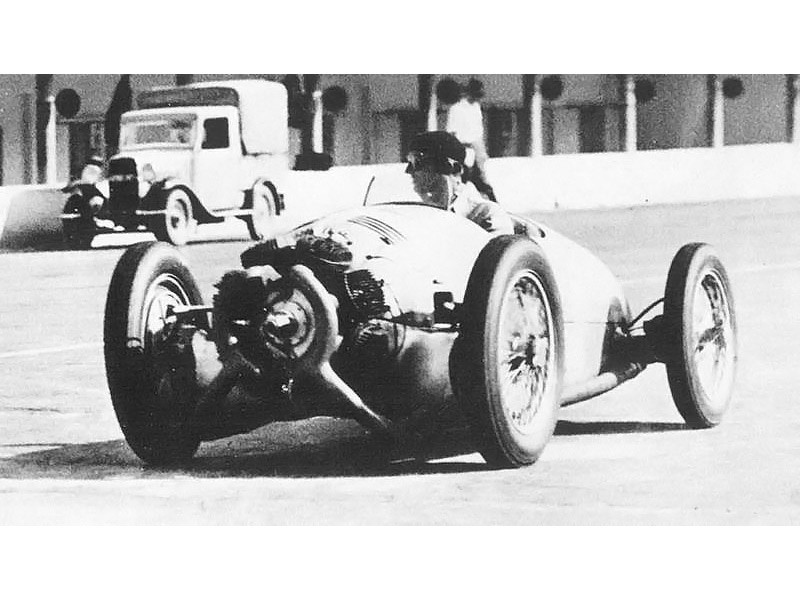

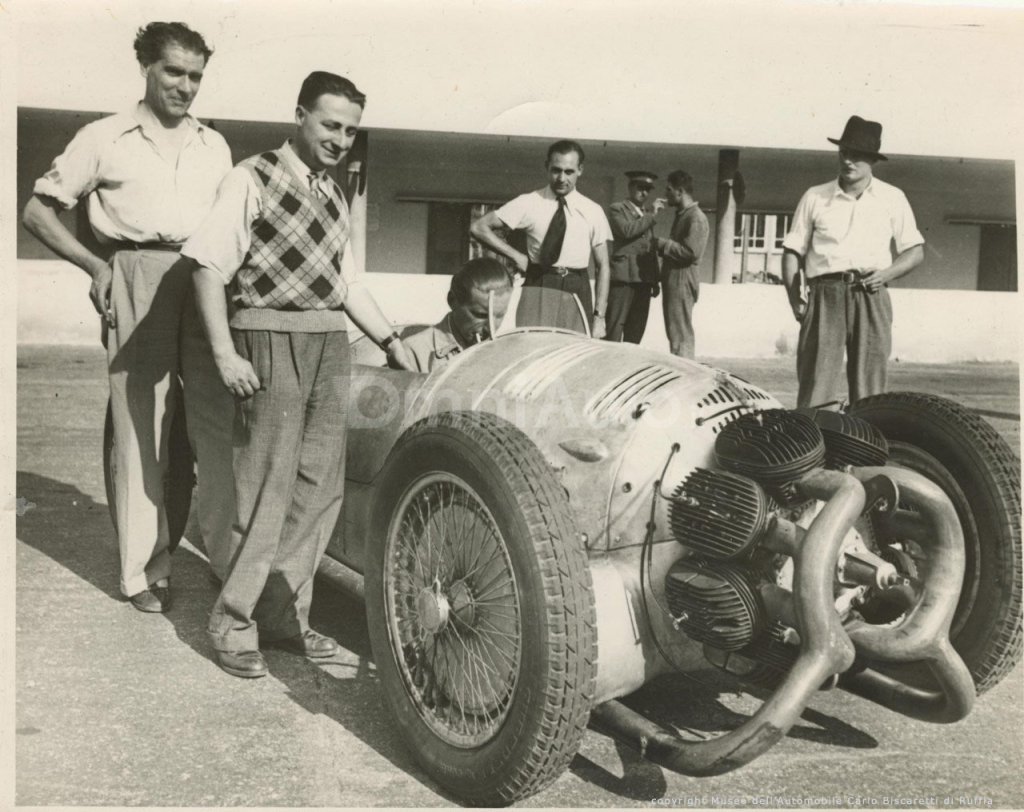

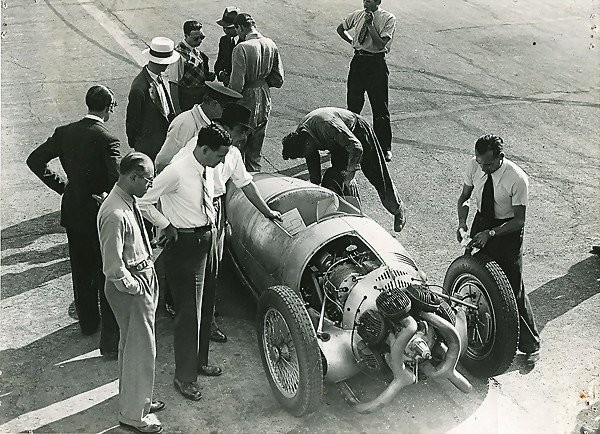

Zwrócił się więc w stronę Alfy Romeo – a dokładniej ich kierowcy, Hrabiego Carlo Felice Trossi. Obiecał on udzielić wsparcia zarówno finansowego, jak i wspomóc przy samej budowie. Pojazd nabierał kształtu w garażu zamku Gaglianco, w północnej Italii. A propos kształtu – karoserią zajął się znajomy Trossiego, Hrabia Revelli. Zaprojektował opływową sylwetkę dla auta, które owiane było tajemnicą i krążyło na jego temat wiele plotek, a pierwszy raz światu pokazane zostało w lipcu 1935 roku. To były testy i sesja kwalifikacyjna do Grand Prix Włoch na torze Monza.

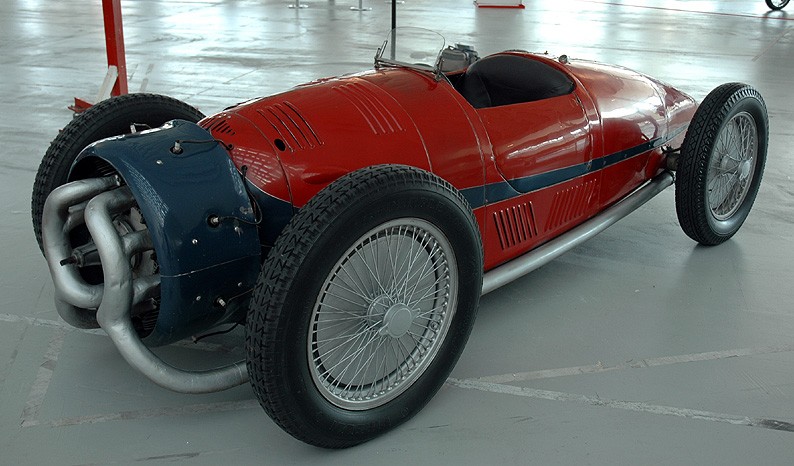

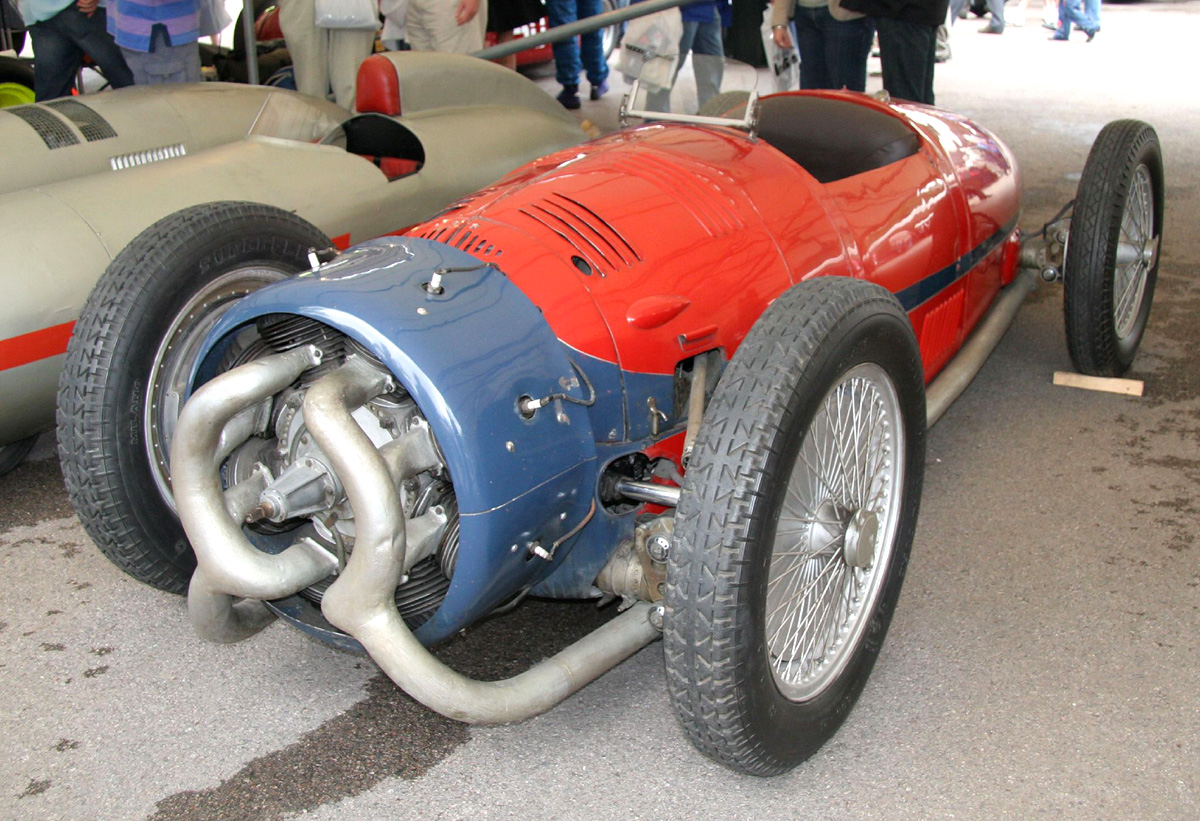

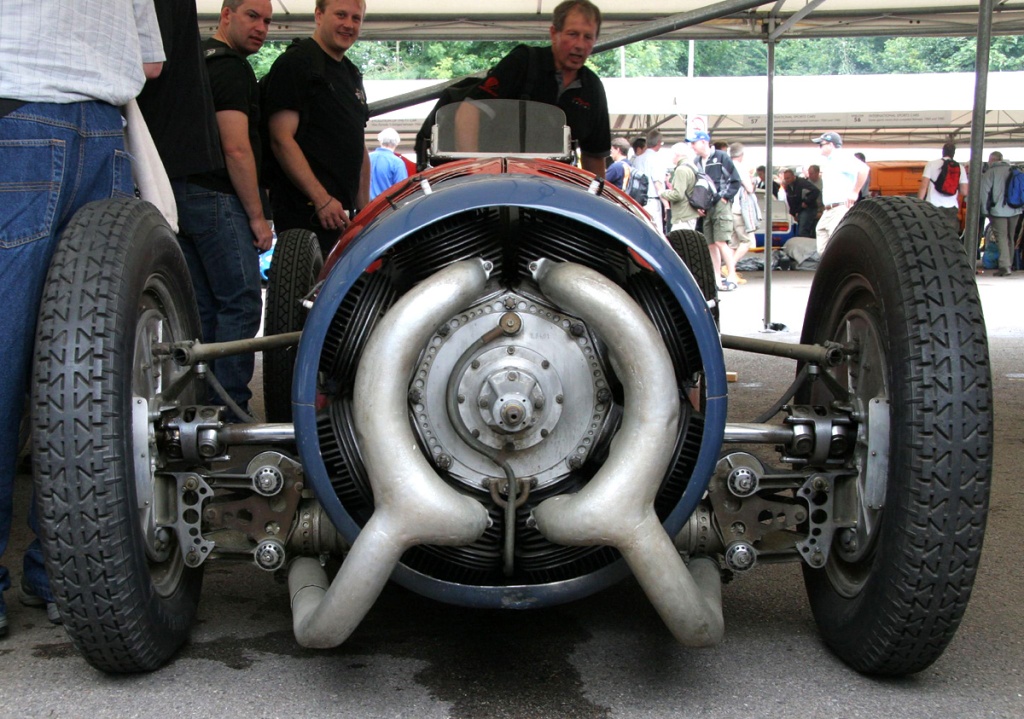

Auto miało chłodzone powietrzem 16 cylindrów w gwieździe – zamontowane na samym nosie auta. Cylindry były zaaranżowane w dwa „rzędy” – dwie „gwiazdy” po osiem – jedna za drugą. Każdy cylinder miał swoją parę. Dzięki temu rozwiązaniu mogły mieć wspólne komory spalania i świece dla każdej pary cylindrów. Wszystkie okalały wał napędowy i – jako, że dwusuw – nie było w nim zaworów. Porty dolotowe znajdowały się przy tylnych cylindrach a porty wydechowe – przy przednich. Wał korbowy składał się z trzech części, a samą skrzynię korbową wykonano z duraluminium.

Za silnikiem znajdowały się dwa kompresory Zoller M160, z gaźnikiem Zenith każdy. Z przodu znajdowała się również para kolektorów wydechowych – poczwórnych – z których odchodziły rury wydechowe, łączące się w dwie rury o imponującej średnicy przechodzące pod autem. Taki układ był w stanie generować 250 koni mechanicznych.

Przenoszonych na koła za pomocą 4-biegowej przekładni. Zawieszenie było niezależne: podwójne wahacze przy każdym z kół. Do tego sprężyny piórowe poprzecznie i amortyzatory regulowane z kabiny auta. Podwozie było inspirowane lotnictwem. Była to rama przestrzenna ze stali manganowo molibdenowej. Z rurek o średnicy 4 cm, a z tyłu i na przedzie nawet większych. Sama karoseria była z lekkich stopów, i za pomocą wkrętów przymocowana do platformy. Auto zmieściło się w 710 kilogramach, i z racji na duże hydrauliczne hamulce przy każdym z kół – było całkiem zaawansowane jak na swoje czasy.

Oczwiście nie mogło to jeździć. Obaj Trossi z Ayminim potrafili osiągać prędkości na poziomie 240 km/h, a ich auto widniało na liście startowej do Grand Prix, ale silnik – mimo, że odsłonięty na przedzie – grzał się jak sam chuj i wykrzaczał świece. To z mniej istotnych problemów. Gorzej, że 75% masy auta znajdowało się na przedzie, i bez przebudowy od podstaw nie dałoby się poprawić właściwości jezdnych, które były niereformowalne. Auto było szybkie na prostej, ale nie potrafiło ani hamować, ani skręcać – dwa manewry, które są całkiem przydatne do zawodów. Stwierdzono, że jazda czymś takim była zbyt niebezpieczna i nigdy jej nie kontynuowano.

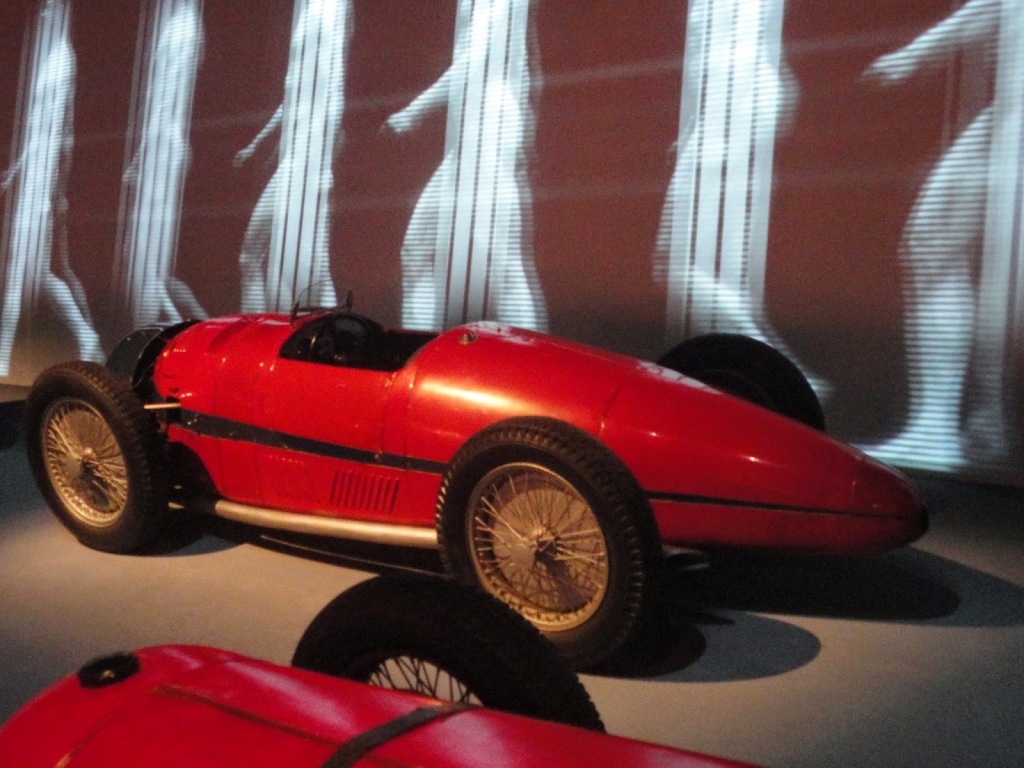

Od tamtego czasu model zamknięto w szopie, a Trossi odnosi sukcesy za kierownicą Alfy Romeo, Mercedesa, czy Maserati. Nawet po wojnie jest najszybszy podczas Grand Prix Włoch, jak również GP Szwajcarii. Ma jednak guza mózgu i 1949 roku umiera, a wdowa po hrabim oddaje jedyny egzemplarz Monaco-Trossi do Muzeum Motoryzacji w Turynie, gdzie podziwiać je można do dziś.

Krzysztof Wilk

Na podstawie: thegoodnaturedfink.wordpress.com | oldmachinepress.com | unracedf1.com | museoauto.com | thegoodnaturedfink.wordpress.com | 360carmuseum.com | sportscars.tv | greasengasoline.wordpress.com | wheelsage.org