I wanted to throw in my two cents for the new series of memes about safe driving… Have you heard the story about little Johnny who kissed a tree? No? Go ahead, make yourself a coffee, and I’ll tell you all about it.

This gentleman here is Ettore Arco Isidoro Bugatti (the one on the left) – his name might sound familiar because it’s suspiciously similar to a certain brand of luxury cars (what a coincidence). He was a Frenchman born in Italy who started a business in Germany. So who’s who? Well, Carlo Bugatti – his father – designed jewellery and furniture in the Art Nouveau style. Ettore’s brother, Rembrandt, was a sculptor. His aunt married a painter, and his paternal grandfather was an architect… who also sculpted on the side. Following the family tradition, Ettore went to the Academy of Fine Arts too. So, like his father, he became a designer – just in a different field.

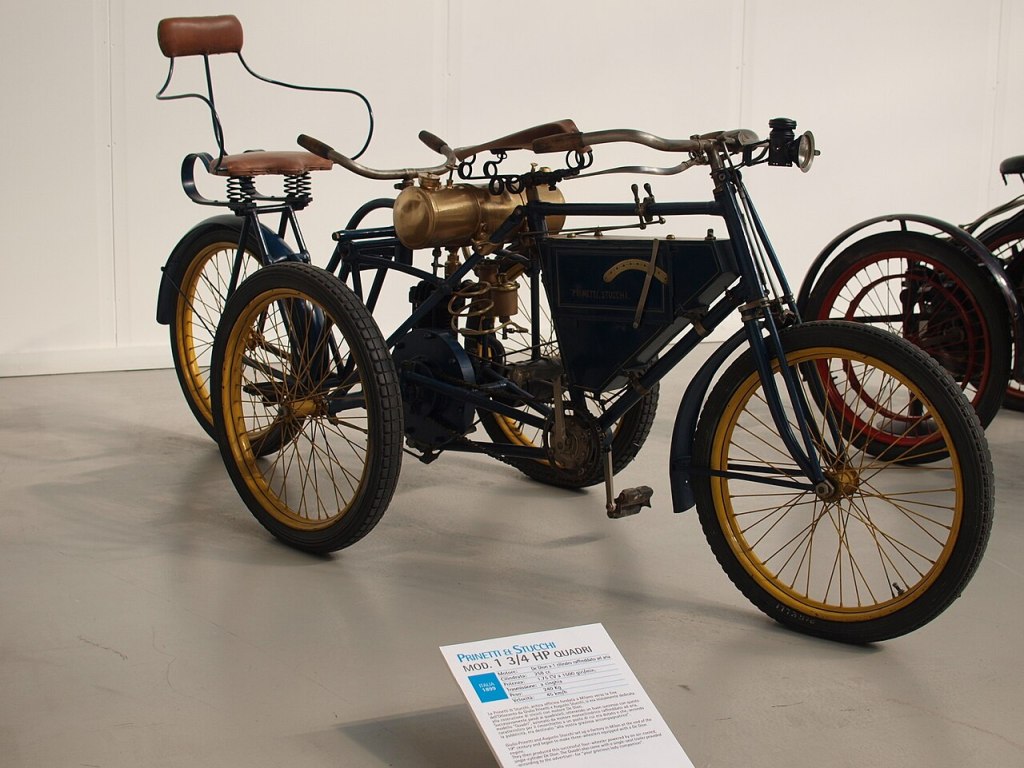

He started boldly – by strapping a rocket engine (not really) to a scooter-like contraption, which he then used to win 8 out of 10 races he entered. That was during his apprenticeship at Prinetti & Stucchi, who quickly realized Ettore had talent. They built that machine for him in 1898 and named it the Bugatti Type 1. He achieved all that before he turned 18… just saying. Not only did Prinetti see his talent, but so did Baron de Dietrich Adrien de Turckheim. The baron came across Bugatti’s latest designs, including a four-wheeled vehicle powered by four engines. Impressed, he offered Ettore the resources to bring his ideas to life. Ettore started designing vehicles for Lorraine-Dietrich, producing models from the de Dietrich Bugatti Type 2 to the Type 7. Somewhere in the middle of this came the Franco-Prussian War, and the company ended up split, with factories on opposite sides of the border – but that’s not important. What is important is that Ettore met Emile Mathis – or rather, Ernest Charles Mathis, a French (now, though pre-war he’d have been German) businessman who, like Bugatti, had a sharp mind (until 1956, when he fell out of a Geneva hotel window, but that’s beside the point). Before that, Mathis collaborated with Ford, and before that, he founded a company with Ettore Bugatti. In 1904, the two left Lorraine-Dietrich and created Mathis-Hermes Licence Bugatti. After two years of working together, they parted ways. Ettore went on to build prototypes for Deutz in his new research facility. Soon after, he became Deutz’s Production Director while simultaneously working on the Bugatti Type 10 in his personal garage. The Type 10 was an inline-four with a monoblock design of his own creation, featuring an overhead camshaft and two valves per cylinder – in 1908! It had leaf springs at the front and no suspension at the rear. Ettore used this car for a significant journey: when his collaboration with Deutz ended, he loaded up his family, piled them into his self-designed car, and headed to Alsace to start his own company.

He made his roots in Molsheim, Alsace – now France, but back then, Germany. Ettore built unbelievably fast cars that were also ridiculously luxurious and technologically advanced. His success in motorsport was nothing short of monumental because his machines were simply the best. The very first Grand Prix Monaco was won by a Bugatti driver. Even now, the revived Bugatti brand produces vehicles that leave everything else in the dust in terms of performance, craftsmanship – as well as price and exclusivity. Personally, there are two models in Bugatti’s history that I have a soft spot for. The EB110, which probably graced the bedroom walls of every ’90s kid, has always had a special place in my heart. The second is the Type 57…

Just like today Bugatti cars often come in numerous variants – frequently produced in small runs of just a few units – the same was true back in the day. For example, this is the Bugatti Type 57 Grand Raid Worblaufen Roadster from 1935, of which only two were ever made. Both found buyers in Switzerland, one of them being Prince Louis Napoleon Joseph Jérôme Bonaparte. Interestingly, the two cars had distinct differences in detail. This one, for instance, is front-wheel drive! In contrast, the other roadster featured a proper rear-wheel-drive setup. But this isn’t the first Type 57 example – before it came the Gangloff Cabriolet. Earlier that same year, at the 1934 Paris Motor Show, the Type 57 Gangloff Grand Raid was unveiled, with Coupe and Sport Saloon versions also introduced.

I’m a bit torn here because the Type 57C Gangloff Cabriolet from 1938 is an absolutely stunning car. The C versions of the Type 57 came about because Bugattis were ridiculously fast for their time… but they could always be faster. Ettore used to claim that supercharging was for wimps, though he did try it once – following the logic that ‚one time doesn’t make you a sellout.’ Only two of these were made initially. However, when customers saw these supercharged versions, they started coming back to Ettore with their new cars, asking to have similar systems retrofitted. So, while Bugatti wasn’t a fan of the idea, when the customer pays, the customer gets what they want. And that’s why I’m torn—because there was also the Stelvio Gangloff, another supercharged beauty. Honestly, I’m not sure I’d be able to pick a favourite between the two.

Apart from the 57C, there were also the S and SC versions, which took their name from Surbaisse Compresseur. These versions were both supercharged and lowered. They featured a dry sump lubrication system because the engine simply wouldn’t fit under the new hood otherwise. To top it off, the front end was equipped with what was practically independent suspension – though Ettore himself had little love for such a solution.

There were also the sportier versions: the 57G, S, SC Corsica Roadster, and Competition, which competed worldwide. However, one of the most iconic Type 57 models is undoubtedly the Aerolithe – a prototype born during the throes of the 1930s economic crisis. The goal was to keep the business afloat, and a bold new project seemed like the way forward. Thus, in 1934, the Type 57 was born. Its popularity surged with the introduction of the sporty variant unveiled shortly after. At the Paris and London motor shows, both models stood side by side. The streamlined, sporty coupe initially bore the name Type 57S Coupe Special but quickly earned the nickname Aérolithe. The project featured a 3.3-liter DOHC inline-six engine and was a direct competitor to the Mercedes 500K and Talbot-Lago. But truthfully, not one of them came close to its daring design. The car’s body was crafted from Elektron, a magnesium-aluminum alloy that was incredibly lightweight and durable – but also highly flammable. Welding the body panels was out of the question, so aircraft-style riveted construction was used instead. Production models, however, switched to aluminum, sidestepping these challenges. Speaking of production models – those were named Atlantic. Initially set to carry the Coupe Aero name inherited from the prototype, the moniker was changed to honor Ettore’s friend, French aviator Jean Mermoz, a pioneer of aviation who tragically disappeared over the Atlantic, reportedly due to engine failure. To commemorate him, the model became the Atlantic Coupe. Only five were ever made: the prototype, two Coupe Aeros built before the rename, and two officially branded Atlantic Coupes.

The prototype shocked and dazzled, but it failed to win over customers. It returned to France, where it was disassembled. Only 11 photographs, one painting, and two schematics of the car exist – yet that was enough to recreate a 1:1 replica in Canada in 2013, a process that took five years. The first Coupe Aero was sold to Victor Rothschild, the 3rd Baron Rothschild. Over the years, it passed through several owners and was eventually sold in 2010 for a staggering $30 million. The second Coupe Aero, also known as La Voiture Noire, is currently lost and estimated to be worth around $115 million. This car was commissioned by a Greek racing driver and uniquely came factory-equipped with a supercharger, making it a 57C-spec vehicle. In 1937, after winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans, Bugatti driver Robert Benoist received this car as a gift. Interestingly, it was never officially registered to anyone. It lacked a legal owner, though it was frequently driven. In 1941, it mysteriously disappeared, leaving no trace.

The third car, a 57S Atlantic Coupe, was owned by individuals who were tragically murdered by Space-Nazis from space that came to us in the 1930s – totally from space. The car, along with the estate it resided in, was later acquired and remains a showstopper at beauty competitions to this day. Although it underwent a series of repairs in the 1970s – where many parts, if not most, were replaced with non-original components – it still stands as a breathtaking piece of automotive history. The last Type 57 SC Atlantic Coupe also survives to this day. Originally built for British pennis player Richard Pope, it featured a slightly redesigned front end. The grille was distinct from other models, and the car lacked front bumper guards. Shortly after purchase, it returned to Bugatti for the installation of a supercharger, upgrading it to 57C specifications. This car endured a minor collision and passed through various owners before finding its way, in 1988, to famed fashion designer Ralph Lauren. Under his ownership, the car was meticulously restored to pristine condition. This particular example has also racked up awards at prestigious car shows, cementing its status as an icon.

Type 57s are still being discovered even today. A few years ago, at an auction held by Bonhams, one of the objects up for bidding was a Type 57S valued at $5 million – found shortly beforehand in an abandoned shed. An earlier discovery was inherited from a deceased owner who had possessed the car for decades. What’s truly remarkable is that the family had always been aware of the car’s existence but had no idea of its true worth. When it finally came time to sell it at auction, the car fetched over $30 million, making it the most expensive car sold at the time, until the Ferrari 250 GTO was auctioned a few years later…

Beautiful cars, yes… What was I saying? Oh right, about safe driving… I’ll get to that in a moment. What connects all these cars? Well, almost all of them – the Type 57s were designed by Jean Bugatti, Ettore’s son. From hie early days, Jean was interested in his father’s work and became an integral part of the business in the 1920s. Even then, he displayed exceptional talent, designing most of the elements of the Type 41 Royale at the age of just 23. As a brilliant designer, he complemented his father, a superb engineer. The 57 Stelvio, Ventoux, Atalante, and Atlantic were his creations. He was also the author of the new generation of independent suspension, meant to replace the fixed front axle. Jean often tested vehicles of his own project, including the 57C Tank, which won Le Mans in 1939. He was driving on a public road, you know, just a typical weekend. A drunk postman on a bicycle was riding down the middle of the road. Despite the Bugatti cruising safely at 200 km/h on a narrow road, it couldn’t avoid the tragic collision with a quickly approaching tree.

So, I say to you all: don’t drive too fast.

And then: never under the influence – not even on a bike.