| Engine | Displacement | Power | Acceleration | Top Speed |

| Straight 4 | 2.0 L | 100 BHP | 12.3s | 167 km/h 104 mph |

| Straight 4 Turbo Diesel | 2.4 L | 90 BHP | 14.1-14.9s | 163 km/h 101 mph |

| Straight 6 | 2.4-2.6 L | 120-136 BHP | 10.7-13.3s | 183-191 km/h 114-119 mph |

| V8 | 3.5 L | 148-190 BHP | 7.1-11.2s | 191-219 km/h 119-136 mph |

The Rover brand was then operating under the British Leyland umbrella, and with the P6 it scored a serious hit. That car notched the first-ever Car of the Year award — and Rover repeated the feat in 1977 with its successor. In 1976, the SD1 made its debut.

The whole British car industry is a saga of highs and lows. Before the Great Depression there were almost two hundred different automakers on the islands… and afterwards? Well, roughly 70% of them went straight to hell. The entire industry was refocused on armaments, and nobody gave a damn about making cars — it was a terrible time for it.

After the war things resurrected somewhat, and the UK became the world’s second-biggest producer of automobiles – only the States outpaced them, but most American cars stayed at home. England was the uncontested export champion until the ’60s.

…Then, at the decade’s end, desperate privatizations were launched to save the auto sector. They accomplished nothing, because Continental Europe and Japan delivered a sucker-punch that British Leyland simply couldn’t survive. They threw more money into the pit, but it was hopeless — management was as competent as that of the Polish Football Association’s, quality control was non-existent, there was a fuel crisis, unions striking… It was literally a circus, like Polish football today. England never really recovered its automotive mojo after that.

That movie of catastrophe still had a few good scenes and some talented actors. By and large it was a tragedy you couldn’t watch sober – but Rover managed to stand out from that general shitshow and build a car you didn’t have to be ashamed of. They even managed to launch a genuinely premium-class model.

Rover actually started in 1878 as a bicycle company. Back then it was Starley & Sutton in Coventry, building motorcycles and bikes – long before the islands caught the bug for modern transport. When they did, Rover went “all in” and it was supposed to be downhill from there. Spoiler alert: it wasn’t.

Rover even came victorious at the legendary 1930s “Le Train Bleu” race, where cars raced trains from Calais to the Cote d’Azur. Together with BRM, they experimented on Le Mans prototypes. They tried everything — and it all went down the drain, because the marque was always on the brink of bankruptcy.

Sporty experiments aside, Rover always had… well, maybe not ultra-luxury DNA, but definitely premium-class aspirations. Models like the Rover 80 or P4 were solid players in that segment. So what went wrong? Money. None of those models were big money-makers. That was Land Rover’s territory — and Land Rovers aren’t exactly daily drivers.

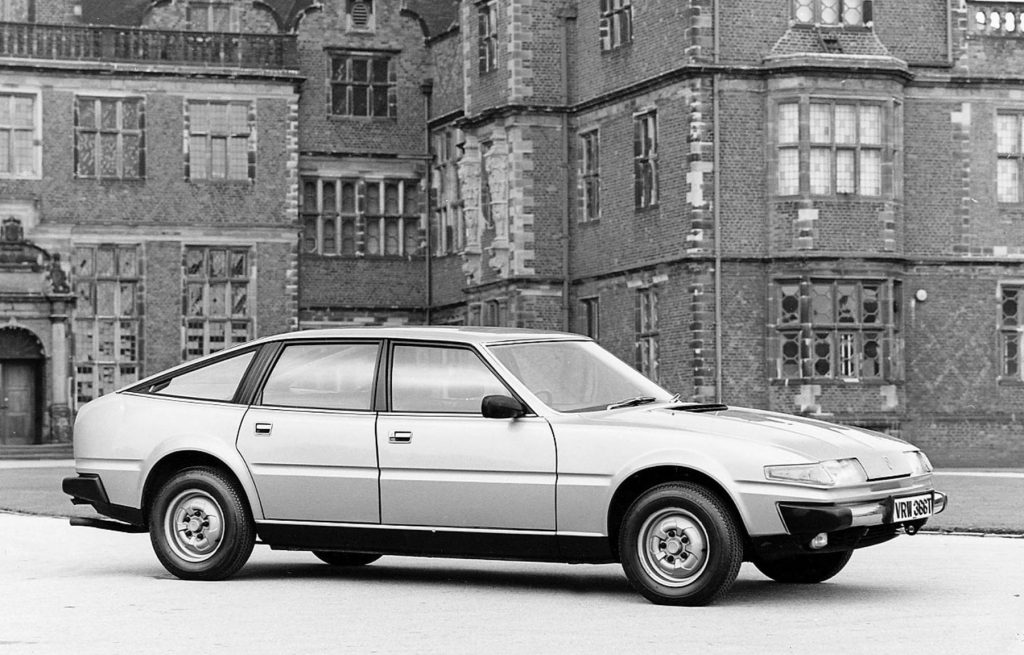

Rover got lumped under British Leyland and the “Specialist Division” was born. Their first model — hence SD1 — was meant to replace the outgoing Triumph 2000 and the legendary P4 and P6. It was billed as “the Rover for the social elite,” a fresh start and trendsetter.

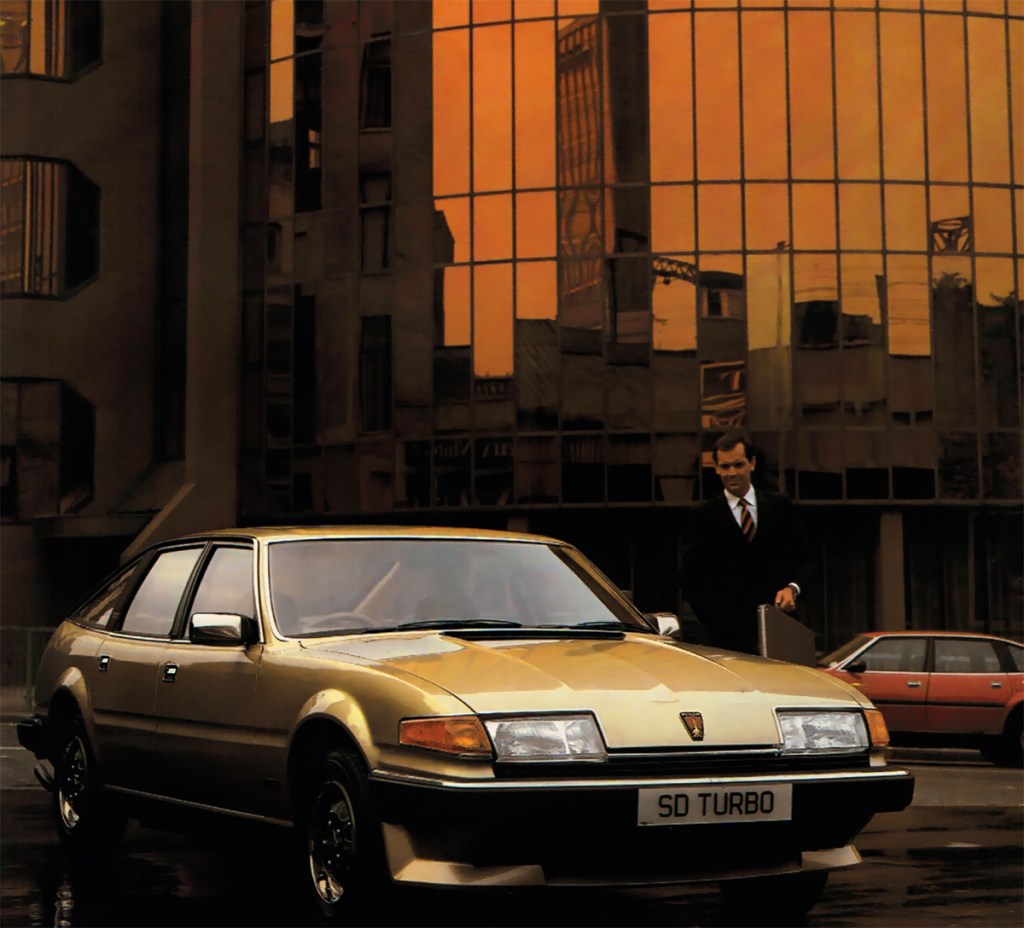

It was a handsome Pininfarina-inspired fastback (think BMC 1800 concept) by Leonardo Fioravanti — Ferrarista through and through, especially the Daytona. Bold for a Rover — practically futuristic. No leather trim. They stripped out all chrome and wood, breaking with British tradition. Hell, they even went hatchback instead of that “wardrobe on wheels”! The dash was a unique two-tier design — never seen on these isles before.

Italian styling influences are in your face: narrow front lamps, a bulging bonnet that screamed Maranello V12. You could spot hints of the Citroën CX or Maserati Indy. Even fifty years later it still looks sharp. It remained a premium car but wore a sports-car vibe — an utter upheaval for a brand for grandpas.

Compared to Fords or Vauxhalls of the time, the Rover looked cosmic. Sleek, cutting lines — pure eye candy. And you could spec a V8 under the bonnet. Nobody else in Britain dared.

Under the skin it wasn’t revolutionary: still had drum rears. The rest of Europe had full independent suspensions and even the P6 had a De Dion rear, so SD1’s live axle was arguably a step back.

But every stick has two ends: SD1 was far cheaper than the P6 and, most importantly, much easier to build. Its McPherson front end handled nicely, and the self-levelling shocks did their job. The lightweight, precise rack-and-pinion steering earned rave reviews.

At launch you could choose anything from a so-so inline-six (2.4 or 2.6 L) to a 3.5 L V8. The V8 was Rover’s own SU HIF6-carburetted unit (later fuel-injected), originally based on Buick’s aluminum 215 Fireball pushrod engine — shared genealogy with Pontiac Tempest, Buick Special, Olds F-85. A small, light yank-derived engine that Rover bought the rights to and built themselves for decades — found homes in Land Rovers, TVRs, Marcoses and Morgans.

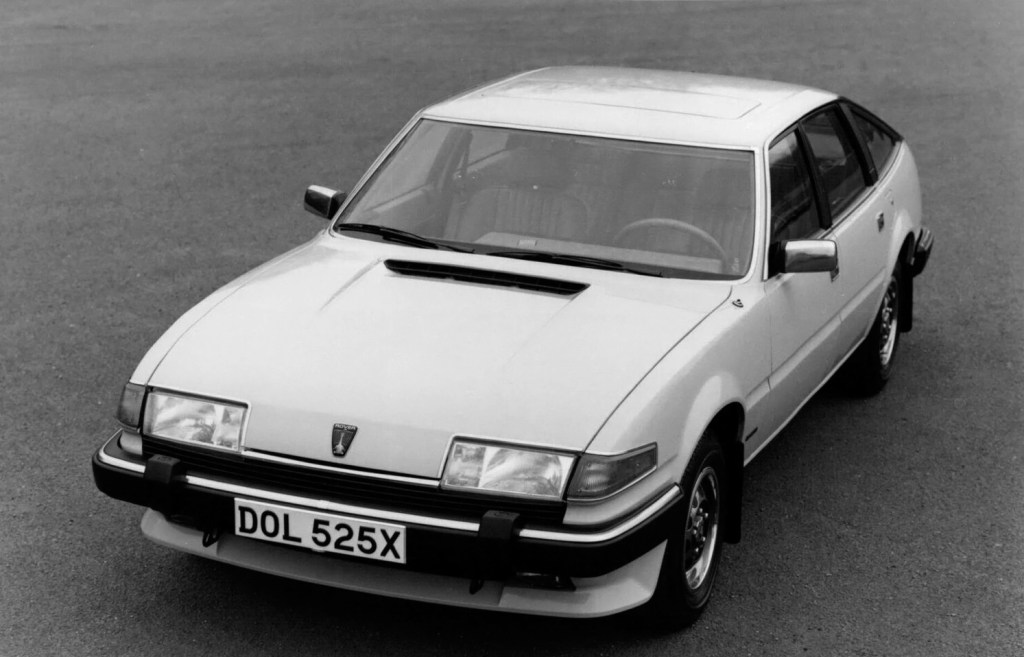

That powertrain lineup sufficed well into the ’80s, until by 1982 they finally gave the aging SD1 a refresh — mainly to address its power deficit. They introduced Straight 4 options to match it against rivals like the Granada. They even offered diesels and nice Vanden Plas variants on both six- and eight-cylinder blocks. Early cars were so-so, but post-’82 you couldn’t complain — though it still wasn’t the ultimate SD1…

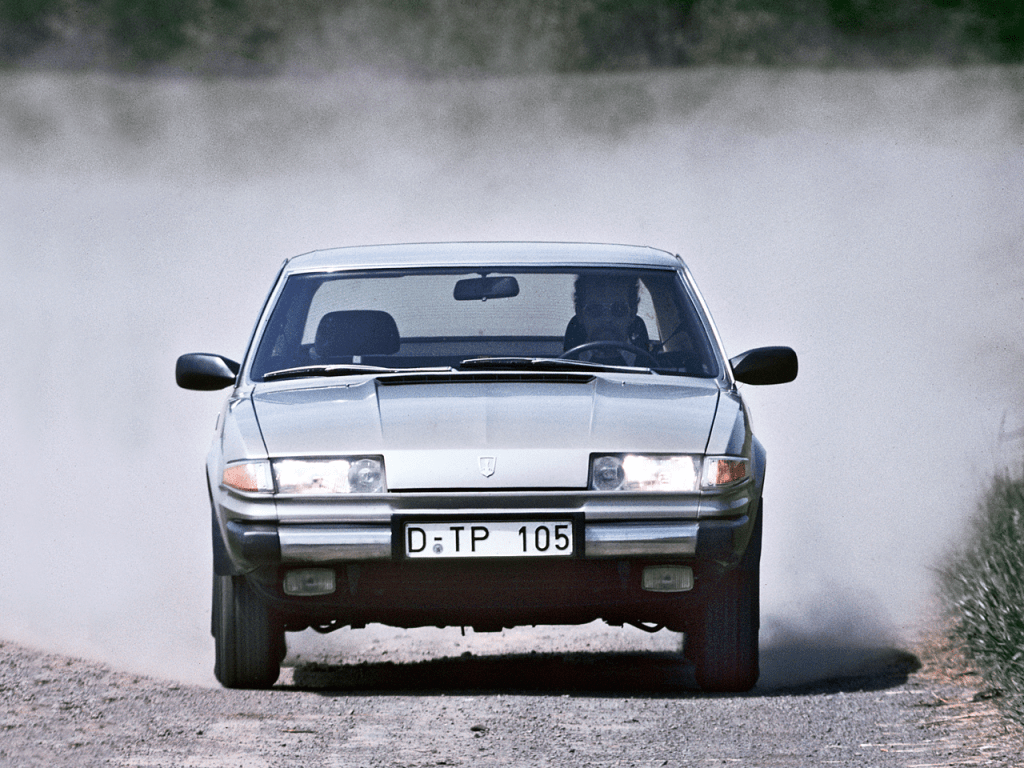

Because in the ’82 catalog it debuted the Vitesse (literally “fast,” originally meant to be called Rapide, but Lagonda held that name). Rover Vitesse was a no-brainer – the same body, front-engine/rear-drive layout, live axle. But it was lowered, had stiffer springs, bigger brakes (four-piston fronts), and an uprated steering rack.

Some say the spoiler reduced drag — others say it didn’t — but it sure looked the business. They raised compression, improved cooling, added Lucas electronic injection, reshaped intake, and reworked the ECU. Suspension tweaks sharpened stability and handling.

The same car suddenly jumped from ~150 hp to about 190. 0–62 mph in 7.1 s — that was class-leading. It was officially the quickest sedan in Britain at launch. The Vanden Plas came fully loaded: leather, wood, Pioneer cassette deck, climate control — all the options you could bolt on, included.

The first SD1s rolled off in 1976 and kept improving. In 1977 it was crowned Car of the Year. Even the cheapest 2.0-liter variants felt premium compared to anything else at the time. They were more affordable yet still boasted quality that rose with the pricier V8 and auto-box models.

These were proper, well-rounded machines: comfortable interiors, bold sporty styling, and credible performance. With the 3500 Vanden Plas and Vitesse, Rover finally had segment-leading cars that, in theory, should’ve turned a profit — backed up by more economical four-cylinders.

SD1 was a TV star too — used by police as pursuit cars. It built a fanbase. Nobody else made a fast, premium family sedan then. You’d have to wait two more years for the first M5 — Rover beat the Germans to it. They set the path.

SD1 was dubbed “the poor man’s Ferrari,” and sure, it may not have been everybody’s dream car, but it carried a chunk of motoring history — and marked a huge leap forward for British cars. In many ways the culmination of Rover and Triumph’s joined efforts, the last “true” Rover to really embody that marque.

Legendary racer Raymond Mays (founder of ERA and postwar BRM) said it was the best car he ever had. Big and heavy? Sure — but it held its own on track and off in rally raids. SD1 won the British Saloon Car Championship in 1984, thrashed everyone in the FIA Touring Car Championship, and grabbed the DTM crown. In its final production year, Kurt Thiim took the DTM title in an SD1. Hell, I’m fat too — but even I’d want such résumé.

Only BMW’s M5 ever threatened the Vitesse in that niche — but SD1 didn’t fall to the M5. It soldiered on for a full ten years, only killed off by the inept Leyland management that built shoddy, ill-fitting cars. That, right there, was Leyland’s coffin nail — and the end of BMC’s glory. And yes, I’ll tell you someday about the worst car in automotive history — and the maker will not surprise you at all…

All British Leyland cars had issues: hot, busted interiors; failing blowers; rust; peeling paint; worn-out trim. A masterpiece on paper but butchered on the line. Rover didn’t save the marque — early SD1s were plagued by poor build quality and perpetual strike action.

SD1 was the last British car to win Car of the Year until Jaguar’s I-Pace in 2019. Remember: SD1 took COTY in 1977! It was also the final “real” Rover. Even the early 150-hp models, maybe a bit underpowered, still torqued hard from low revs. A collector’s gem — and if it isn’t cheap now, it never will be.

Krzysztof Wilk

All credits to: R Nicholls – Supercars | M Buckley – The Complete Illustrated Encyclopedia of Classic Cars | D Lillywhite – The Encyclopedia of Classic Cars | autozine.org | supercars.net | carandclassic.com | silodrome.com | wikipedia.org