Eberhard Schulz to był niemiecki stylista samochodowy… Dziękuję za uwagę – zobaczymy się za dwa tygodnie.

…

…

… Nie no, żartowałem. O panu Schulzu warto wspomnieć, bo jest jedną z bardziej zdolnych postaci w motoryzacyjnej historii. Jeśli ja was nie przekonam, to może suche fakty będą silniejszym argumentem. Chłop dostał ofertę pracy w dziale designu marki Porsche ZANIM jeszcze skończył edukację – a dostał tę robotę, bo we własnym garażu (właściwie jego rodziców, którzy używali tego miejsca jako pralni) wykonał auto pokazowe inspirowane Fordem GT40 i pojechał nim do ich siedziby, gdzie wszystkim szefom popuszczały zwieracze. Nie miał papieru z uczelni i jego CV szczerze nie zachwycało, a dostał u nich pracę wyłącznie za umiejętności jakie potrafił zaprezentować w praktyce i to bez zaplecza. Prawie dekadę spędził w tym biurze, aż zmienił barwy na firmę bb, zajmującą się głównie tuningiem, ale nie tylko. To tutaj Schulz zyskał swoją reputację.

W bb maczał palce przy powstaniu projektu auta dla Mercedesa, i które miało zastąpić legendarne 300SL. Miało naklejki Merca, tak – ale sam zamysł i prototyp powstały w warsztatach bb. Swoją drogą, zajebista maszyna – jeszcze kiedyś o niej napiszę. To na bazie tego pojazdu, po otwarciu własnego biura projektowego, Schulz stworzy swoje pierwsze auto z prawdziwego zdarzenia. Finalnie powstanie około 30 egzemplarzy, wersje spyder, Mercedesy, prototypy – wszystkie Isdery 108i miały V8 Mercedesa o pojemności co najmniej 5-litrów oraz mocy do 400 koni w wersjach AMG. Srogie bydło.

Dlaczego Mercedes powstawał w zakładzie Isdera? Filozofia tej niszowej marki była taka, że wypuszczali na rynek auta, na które duży Mercedes by się zdecydował – gdyby w dupie mieli te konwenanse: marketing, finanse, ekologię, normy emisji – całe to pedalskie pierdolenie. Do zakupu produktów z ich katalogu prowadziła tylko jedna droga: zagadać bezpośrednio z właścicielem firmy – i rok oczekiwania to była norma. A auta Isdera robiła bezkompromisowe: odważne w designie, z mocarnymi osiągami i luksusowym wnętrzem. 3 razy „tak” – przechodzisz do finału. Ten samochód miał wszystko. A w 1993 roku pokazano następcę.

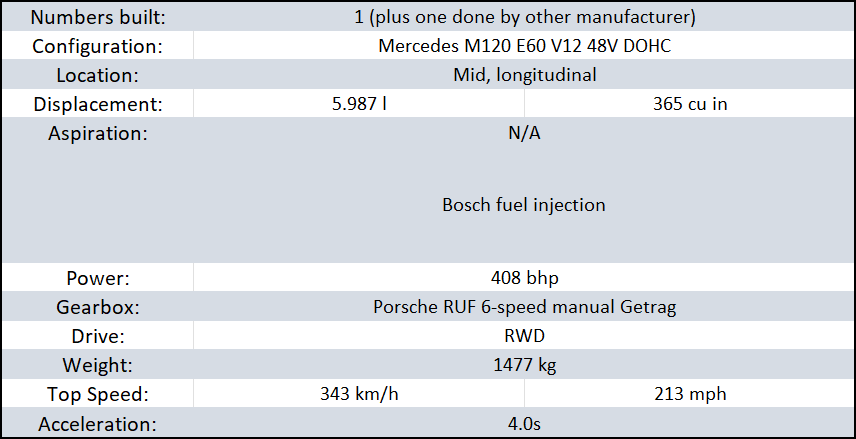

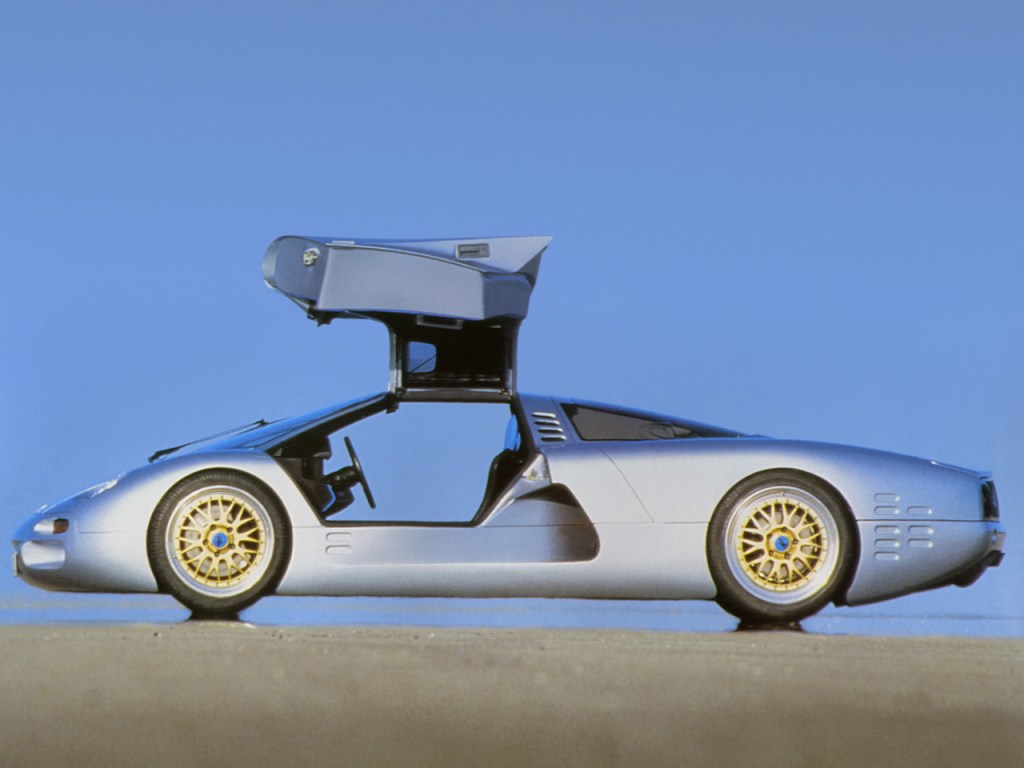

Na targach samochodowych we Frankfurcie w 1993 roku zaprezentowano model Commendatore 112i… i ło, kurwa! Silnik V12 Mercedesa robił solidne 400 koni mocy i miał spore zapasy – mógł spokojnie wydać nawet 150 więcej, gdyby chcieli. To znaczy, że auto rozwijało prędkości do 340 km/h (212mph) i nie musiało zaraz iść do remontu. W tamtym okresie to było niesłychane, a dla tego V12 to było zero wysiłku. To samo serce później jeździło w S-Klasie, ale i ze znaczkami Pagani – i dalej dawało radę. Super sprawa. Serio – polecam.

Do tego skrzynia Porsche po modyfikacjach od RUFa – 6-biegowy manual na bazie 5-biegowej przekładni. Producent deklarował 4,7s w nadświetlną, ale Isdera przekracza pierwszą setkę w 4,2 sekundy. W ogóle, wiele elementów pochodzi z Porsche. Samą budę ręcznie wykonano z włókien węglowych i GRP, ale układ zawieszenia i hamulce z ABSem były dzielone z Porsche 928, a podnoszone lampy wyciągnięto wprost z modelu 968. Auto było wyposażone w podnoszone drzwi, jak w Gullwingu – więcej: miało pokrywę silnika otwieraną w ten sam sposób! Aktywne zawieszenie obniżało auto przy większych prędkościach i odpalało hamulec aerodynamiczny, kiedy trzeba było. Kierowca, nie miał co prawda lusterek bocznych, ale miał za to JEBANY PERYSKOP!

I miało być tak pięknie… To auto zasługiwało na swoją szansę, niestety – podczas rozwoju prototyp miał wiele opóźnień, jak również brak wsparcia finansowego zmusił firmę do ogłoszenia bankructwa i projekt wyrzucono na śmietnik po powstaniu jednego egzemplarza. Co prawda powstała druga sztuka, ale Isdera się jej wyparła. A ten oryginalny? Trafił do rąk prywatnych metodą kupna-sprzedaży i przypudrowano mu nosek. Po machinacjach wyciągał 370km/h za pomocą V12 o 610 koniach mocy – i po tych zmianach trzeba na niego mówić Silver Arrow. Od zwykłej Isdery, Silver Arrow różni się normalnymi lusterkami zamiast peryskopu oraz znaczkami Mercedesa – również na podmienionych felgach. Ciekawostka – ten jedyny egzemplarz doprowadzono do oryginalnego stanu i w zeszłym roku sprzedano na aukcji RM Sotheby za grubo ponad milion starych erło.

Isdera w pewnym sensie łączyła w sobie całe piękno motoryzacji do tej pory. Nazwana po panu Enzo „Il Commendatore”, korzystała z najlepszej niemieckiej technologii, zasilana wspaniałym V12 Mercedesa, stała na zawieszeniu rodem z Porsche. Jeden wielki hołd motoryzacyjnej historii, i z dumą wkraczał w świeżo odkryte rejony 200 mil na godzinę. Auto miało rywalizować w 24-godzinnym wyścigu Le Mans, ale gdy bańka spekulacyjna prysła – marzenie Eberharda Schulza również w pizdu prysło.

Krzysztof Wilk

Na podstawie: favcars.com | wheelsage.org | wikipedia.org | ultimatecarpage.com | autozine.org | topgear.com | rmsothebys.com | supercars.net | motortrend.com | motor1.com | thedrive.com | supercarworld.com | M Buckley – The Complete Illustrated Encyclopedia of Classic Cars | instagram: remidargegenphotographies, kirin_cars, carenthusiasts, danielzizka, mauricevolmeyer, machinistic, sunroofdelete, popz.s, coches.site, abdielnfs, ste19bozzy92, automotived, officialoctanemagazine, nostracarmus, tdautophotog, onlyexclusivecars, mauricevolmeyer, bigboybenzes