| Engine | Displacement | Power | Acceleration | Top Speed |

| V8 | 3.5 L | 250-340 BHP | 250-257 km/h 155-160 mph |

Motorsport was the obvious driving force behind sales. That’s how it was, is, and always will be. Every serious player knew that. The British Motor Corporation had success with that strategy through its Austin Rover and British Leyland brands. In British racing, there were still old Triumph Dolomites going around — so, come on… And just then, the engine size limit was raised to 3.5 liters.

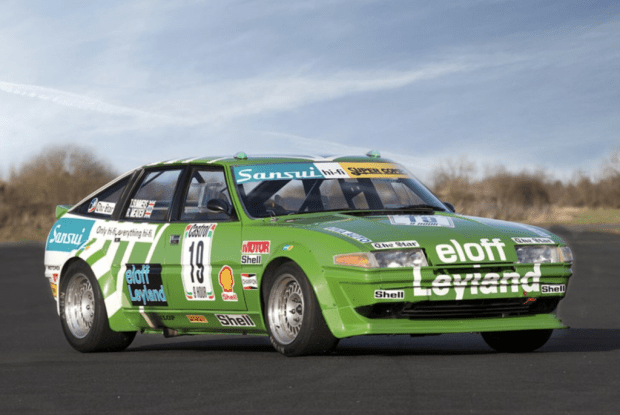

British Leyland tried to cash on racing, and in the ’70s, the obvious choice was the Rover SD1 for touring car competitions. The problem was that folks in the BTCC started whining, talking crap when the car exceeded their beloved 3-liter limit. They were afraid of American competition, but in the end, they allowed the Rover 3500 in under Group 1 rules.

Might have seemed like a shining days then — but that was just the beginning of their misery and torment. The reason was plain and simple: money. I mean, if you want to go racing, it helps to actually have some, right? And that was always a problem for them. So British Leyland wanted to race… but with no program, no engineering support, and a car built on a shoestring. Work on the car began both within the company and with private teams modifying their own vehicles alongside Rover’s efforts. Group 1 was a relatively strict category, so the resulting machines were fairly similar technologically.

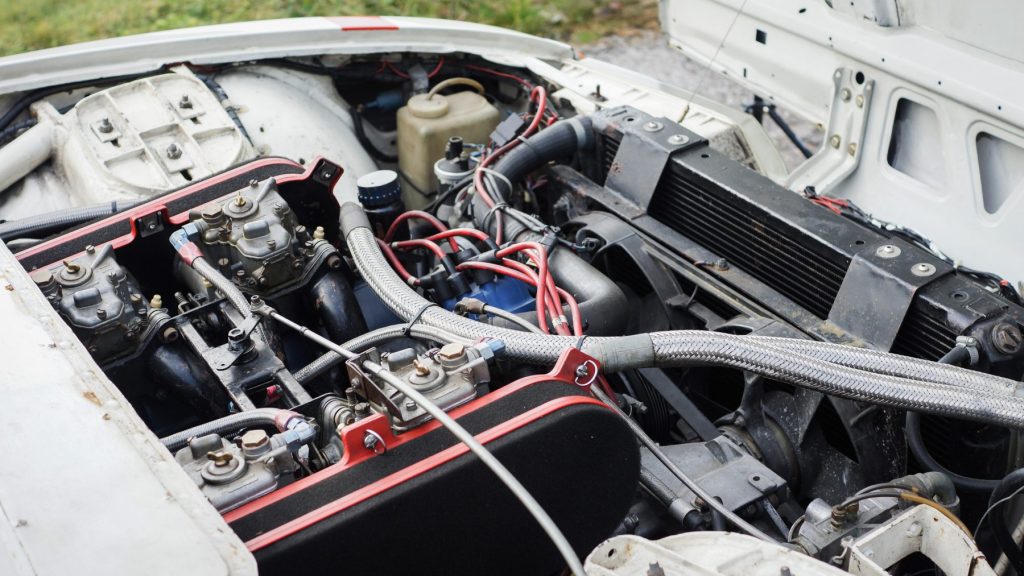

Race modifications focused mainly on upgrading the suspension and brakes. The motorsport-spec Rovers also got shorter gear ratios. They went on a diet to drop as much weight as possible. The V8 had a light-alloy block and still breathed through a pair of carbs, but Rover’s engine was good for a minimum of 250 horsepower. Didn’t matter if it was a privateer car or one from British Leyland — they were very much alike.

The road SD1 was never seen as a motorsport contender, but truth be told, it was a perfect fit. It had great aerodynamics and a simple enough undercarriage that it would be such a waste not to take advantage of it. Most of the race prep happened in the BL Motorsport garages with Dave Price Motorsport help. These were guys with F3 experience, working with drivers like Nigel Mansell. Later on, they would even play a part in the 1989 Le Mans victory. McLaren F1 GTR won that one for the Sauber-Mercedes team, bagging both the drivers’ and constructors’ titles. They were winning in Italy too… well, you get the story. These guys knew racing — that’s the point. And they had to, because they were up against beasts like the Ford Capri and the Mazda RX-7 TWR.

And a good car it was — but not as good as the Capri. The first events ran with a 250-horsepower Rover 3500 S. Not good – not terrible, I’d say. Brands Hatch ended with a solid first place after a strong race in the rain — and the car showed promise. They managed a similar success at Donington, this time with F1 world champion Alan Jones behind the wheel.

The Rover was finishing high up, just not quite at the very top. And of course, that wasn’t enough. The problem was in constant mechanical failures, especially in the drivetrain. So they called in a second opinion — Tom Walkinshaw. Not just a talented driver, but a brilliant team manager. Walkinshaw quickly launched his program, Tom Walkinshaw Racing, and his Rovers hit the top five times that season.

His verdict? “The Rovers are too slow and the engine keeps shitting itself.” He wasn’t wrong, alright. He’d been through the same thing with the Mazdas — and he sorted that out. He told them he’d fix the Rover, but he’d charge £1,000 for every tenth of a second shaved off per lap after his upgrades. They swapped the cats, worked on the suspension, said their prayers… And got pole position for Silverstone race. Rover had to pay up the full £20k — the car was nearly three seconds faster. Even Walkinshaw’s own Mazda had trouble keeping up — and he done good shit on that too.

They also developed a Group 2 version before their contract with British Leyland expired. Group 2 allowed more freedom, so they ditched the carbs for a set of quad-barrel units, gaining a clean 100 horses. That required wider tires and fatter fenders. These cars even entered some endurance races. The TWR collaboration was a game-changer. Walkinshaw breathed new life into the SD1.

Next season, the Rovers ran in full TWR colors. Walkinshaw’s team had a stacked deck — they ran both Mazdas and Rovers side by side, and even fielded an Audi 80 GLE with none other than Stirling Moss behind the wheel. It was his first real comeback after his 1962 crash at Goodwood, where he wrecked his Lotus and spent a month in a coma. And the TWR Rovers? They started winning — regularly. Double podiums, clean sweeps — both 1981 and 1982 were great seasons for SD1 drivers. TWR also prepped rally versions, but those never matched the performance of their track-spec counterparts.

1982 was especially big, with the debut of the Vitesse road car — new suspension, fuel-injected V8. In 1983, the new Group A regulations came into effect, so TWR had to build a fresh machine based on the Vitesse. That was the real shit — and eligible for everything from touring car races to 24-hour marathons and rally events.

It wasn’t just the engine that got an upgrade — the whole platform did. That excuse for spoiler from the road version was binned, and the race car got active aero that actually produced downforce instead of just the looks. That helped — because stock SD1s liked to launch into orbit under hard acceleration. The new version stuck to the road. Group A allowed more flexibility in brakes, suspension, driveline, and rear-end design.

Walkinshaw couldn’t build the cars alone, but he had help from Austin Rover Group Motorsport — they divided the work just to make the season in time. Of course there were problems. The plan was to break 250 horsepower with the new injection, but the rules clamped down on engine mods, exhaust manifolds, and intake design. It was hard to even match the power the old carb-fed engines made — let alone surpass it. So they threw those injectors in the bin and swapped in something totally different — and better. The injectors were key to performance, and early on, they did the job.

The season opened at Silverstone — and the three SD1s swept the podium. They dominated the whole BSCC format. Won all 11 races. BMW started whining about “illegal fenders” that didn’t match the road car. Well… yeah, they didn’t XD And Group A said bodywork had to match homologation. So the organizers erased all of TWR’s results that season. They would’ve won the title, but instead it went to Andy Rouse in the Alfa Romeo GTV6.

Rover also did well in France — but that turned into a circus with extra ballast penalties. Technically they followed Group A rules too, but if you won a race, you had to add weight for the next one — which opened the door to all kinds of games. You could throw a race on purpose to get a better shot at the one after. You never knew who was driving at 100%, and who was just coasting. One day you’d win — next day, you’re last.

Don’t even get me started. At one event, Rover got disqualified because they had to push-start the car. Nope. I’m done – not talking about that anymore. Just know they ended the season with 209 points and fourth in the standings. Next year, the project kept going, and honestly, the biggest improvement was in the driver’s seat — they swapped out René Metge for Jean-Louis Schlesser for some great performances. He could totally dominate certain events, but that year, Peugeot was just stronger.

As for rallying — the first SD1 was built for the Peking to Paris Rally, and it would’ve raced, had the event not been cancelled. Rover was pissed — the car was ready. It passed through a few hands until it ended up with Ken Wood. He entered it in the Scottish Rally Championship, but didn’t know the car well, so instead of pushing, he went for safe points…

… and the man finished second in that event. Sure, it was 1983 and the car was old — just a standard SD1 3500. But when it turned out to be a surprise hit, they upgraded it to Vitesse spec. It had 320 horses at least. In 1984, he won the championship — maybe with an overpowered lump the size of a wardrobe, but at least with no 4×4 (even though it got into mainstream by then).

Maybe it never truly dominated any one series for long, but the Rover SD1 became a motorsport legend — in both British and French racing. And there was a time when, after their circuit careers ended, retired SD1 race cars in private hands kept rallying. It was one of the best performance cars — not because it was the fastest, but because it was so versatile. You could turn a Rover into anything. A personal luxury car, a sports car, a street racer, a muscle, a rally monster, a touring racer… anything you need.

Tony Pond won the 1985 World Rally Championship Group A title in the SD1 — just before Rover switched to competing in Group B with the Austin MG Metro. Thanks to these models, Rover bagged titles in DTM, BSCC, and the RAC Tourist Trophy. The SD1 won in ETCC, FIA TCC, and was fastest in class at Bathurst 1000. It still has a fanbase today, and you can catch it at historic events.

Krzysztof Wilk

All credits to: ultimatecapage.com | supercars.net | touringcarracing.net | carandcassic.com | bringatrailer.com | silodrome.com | wikipedia.org