To jest jeden z bardziej radykalnych supersamochodów jakie powstały, a to dlatego, że jest zrobiony z zupełnie innym podejściem. Zwykle projektanci zajmują się superszybkim autem na drogi, i na jego podstawie budują maszynę do motorsportu. Porsche nie dość, że zrodziło się na torze wyścigowym, ale cykl jego życia wyglądał w ten sposób, że z wyścigówki poskręcano auto drogowe, które potem zamieniło się w wyścigówkę, która potem wracała na drogę… i tak do zajebania.

Zaczęło się od modelu 956 wyścigowego Porsche – pojazdu stworzonego z myślą o Le Mans. Te auta – wraz z 962, który je zastąpił – robiły wszystkich w Grupie C, kurwa, na haxach. Maszyny Porsche dominowały przez dobrą dekadę – wygrały mistrzostwa 5 razy, a 24-godzinny wyścig na torze Sarthe: 6 razy. 10 razy z rzędu zwyciężyły w Mortal Kombat. Oni tam rywalami pozamiatali podłogę, zniszczyli ich totalnie. Oba modele były też jednymi z najpopularniejszych aut wyścigowych – 150 ich powstało tylko do wyścigów, i wiele trafiło potem też w obieg. Porsche nawet bez problemu udostępniało klientom części zamienne do nich. To była woda na młyn… i supersamochody stały się nową modą, a na bazie samego tylko 962 powstało kilka różnych samochodów na drogi publiczne.

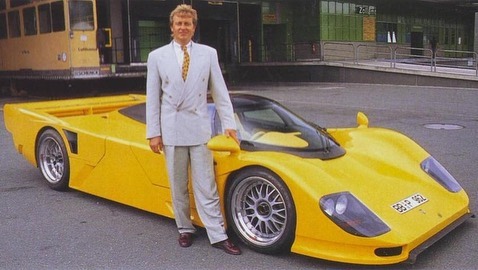

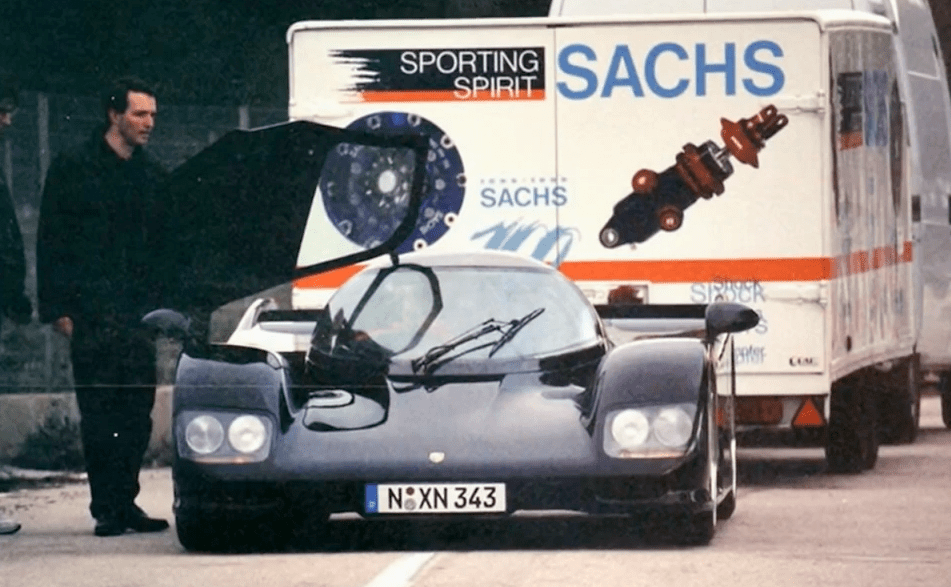

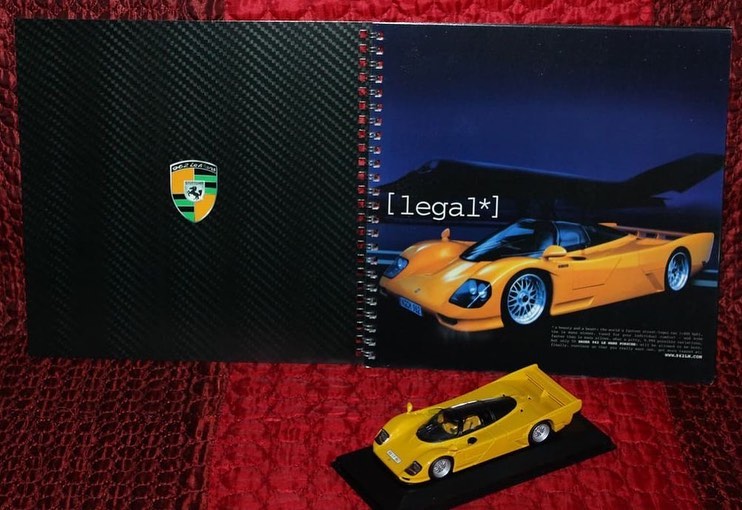

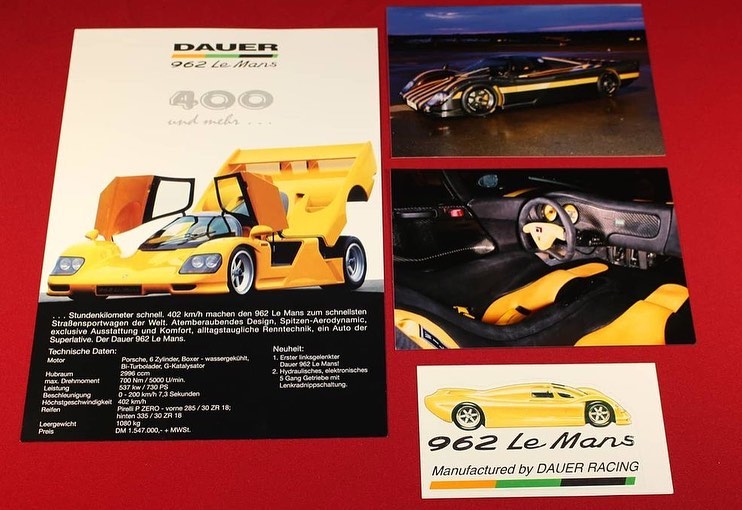

Jochen Dauer był bardzo szybki za kierownicą Porsche 962C, którym zwyciężał w legendarnej już Grupie C. Format jednak dobiegał końca (zakazano turbów), a Dauer widział w wyczynowym aucie potencjał na drogi. Jeszcze w 1991 uzyskał 5 nieużywanych nadwozi, i rozpoczął pracę nad czymś, co miało się stać Dauerem 962 LM. Plan był prosty: zostawić jak najwięcej, i jak najmniej spierdolić. Stalowa rama przestrzenna to właściwie 100% auto wyczynowe, bydlacki układ hamowania też praktycznie w niezmienionej formie, Twin-Turbo również pochodziło z torowych egzemplarzy. Pierwsze auto pokazano w 1993 we Frankfurcie.

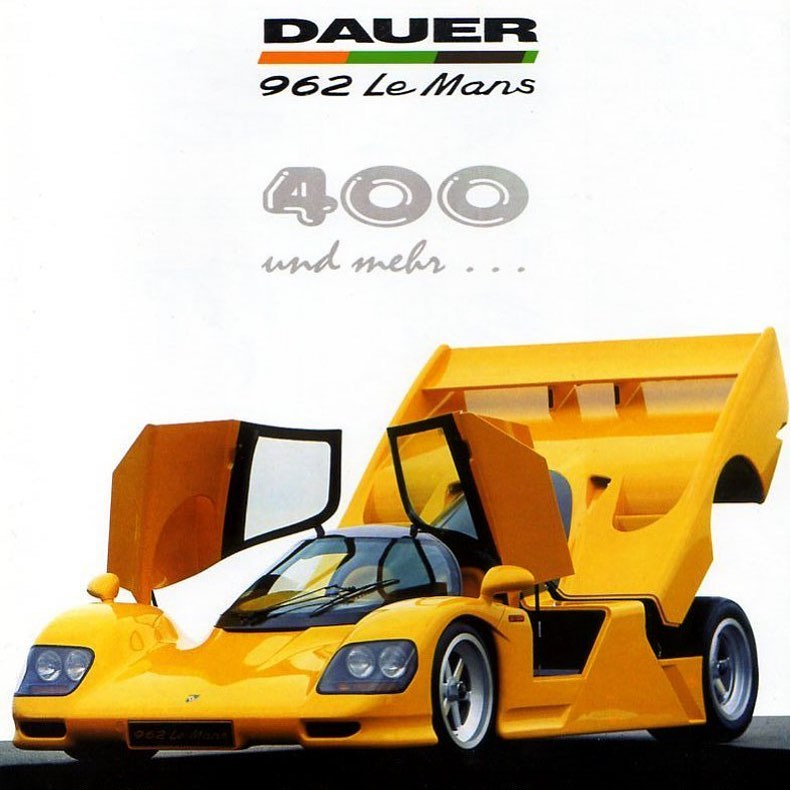

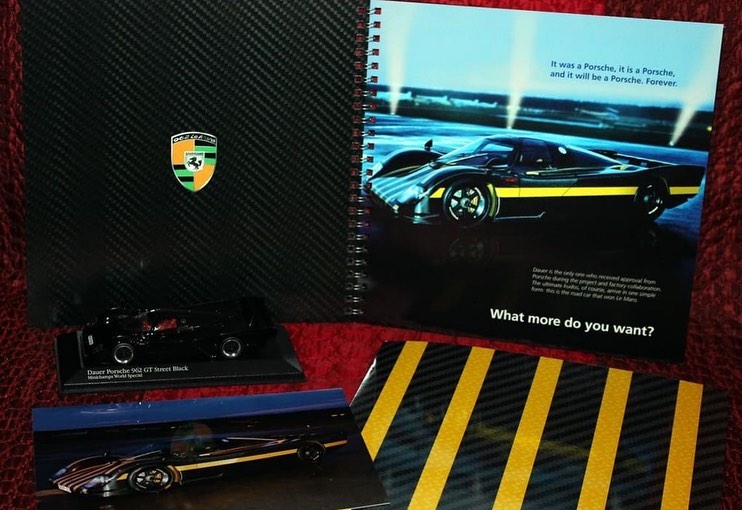

Dauer stale otrzymywał wsparcie Porsche. Nie dość, że dawali mu części, których potrzebował, to zawsze mógł liczyć na dobrą radę doświadczonych inżynierów. Gdy kształtu nabrał egzemplarz z auto show we Frankfurcie – został on poddany gruntownemu przeglądowi wykonanemu przez Norberta Singera z działu technologii motorsportu Porsche. No… zachodzi podejrzenie, że chłop mógł znać się na rzeczy. Co stwierdził: że jego zdaniem auto się nadaje na wymiatacza w klasie GT1 już w takiej formie, jakie było – jakie tam stało. Aby zostało dopuszczone, należało wykonać drogowe odpowiedniki w ilości sztuk 1. GT1 to była fajna zabawa, bo – w odróżnieniu od Grupy C – zachęcała do eksperymentowania z technologią na drogi publiczne, efektem czego powstawały “odważne” supersamochody lat dziewięćdziesiątych.

Z Singerem u steru, Porsche zaangażowało się w projekt jeszcze bardziej. Chcieli zobaczyć pojazd Dauera na torze, i dali mu pełne błogosławieństwo. Można było się tego spodziewać, bo przecież to właściwie było Porsche. Najwięcej prac ludzie mieli z dostosowaniem aerodynamiki. 962C większość docisku uzyskiwało za pośrednictwem tuneli kierujących powietrze pod pojazdem (i model 962LM też je miał, ale do wyścigu już nie mógł). Zasady GT1 wymagały kompletnie płaskiego spodu auta, więc tym razem by to nie przeszło. Odpowiedzi należało szukać w zmianach w karoserii.

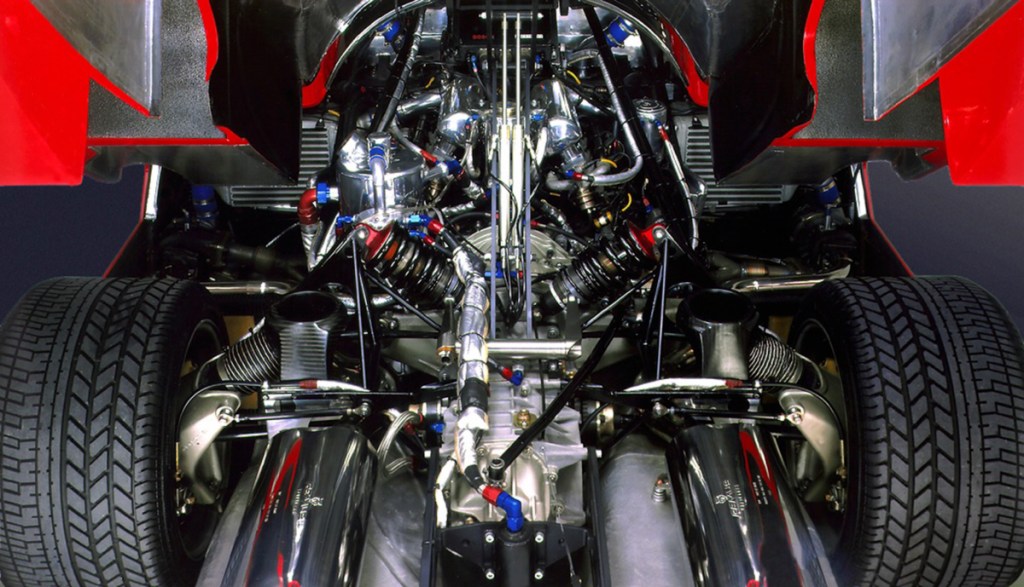

Pod skorupą z kevlaru Dauer niewiele się od 962 różnił, tak naprawdę. To był aluminiowy monokok rozpędzany za pośrednictwem solidnych 3 litrów ułożonych na płasko. To był ten sam silnik, co w drogowym aucie. Bardzo podobny. Wyścigowy wariant musiał być wyposażony w odpowiednie zwężki dolotu, przez co moc zamykała się w 600 kucach. To i tak więcej niż auta w byłej Grupie C. Tym też Dauer przyciągnął zainteresowanie Singera. Auta mogły być raz, że mocniejsze – a dwa, że lżejszejsze – więc Singer miał czym się pobawić.

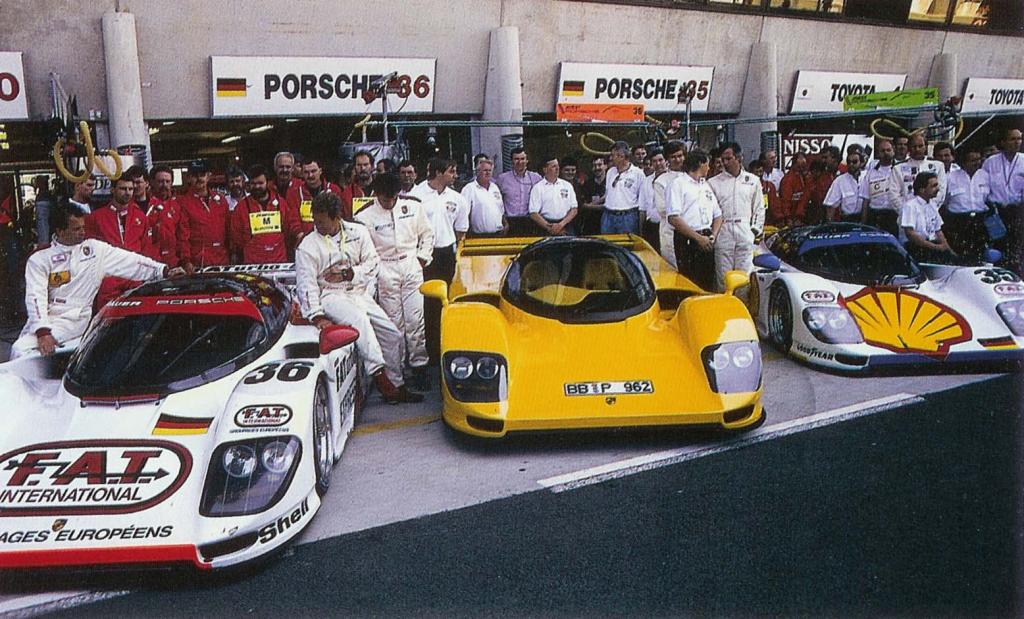

Chciał wysłać to cudo na 24-godzinny wyścig Le Mans, i ostatecznie dwie sztuki podjęły wyzwanie. Porsche zajęło się obsługą pojazdów i jeden z nich wyciągnął trzeci czas w przygotowaniach do eventu. Do zawodów stawały konstrukcje z nieistniejącej już Grupy C, jak i nowoczesne prototypy LMP1. W takim gronie Dauery zakwalifikowały się na 5-tej i 7-ej pozycji. Auta traciły pola w wyścigu, starając się dogonić Toyotę Grupy C, ale Japończycy mieli problem z przeniesieniem napędu – coś tam w ich skrzyni nie tentegowało. Porsche ten moment wykorzystało, i Dauer wrócił na prowadzenie. Pierwszy egzemplarz dokończył wyścig na pierwszej pozycji, a drugi dojechał na trzecim miejscu (drugim w swojej kategorii).

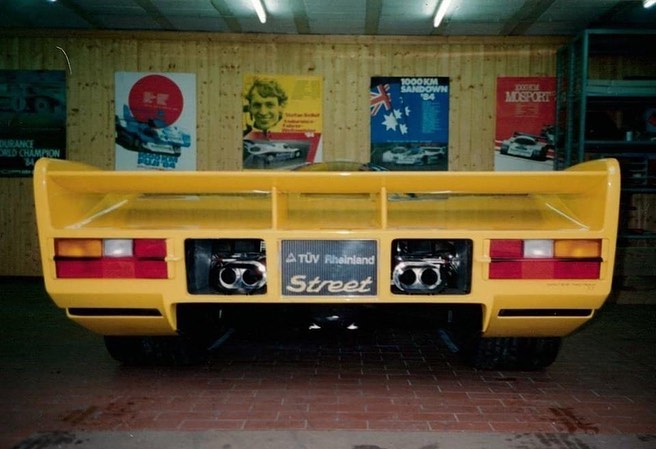

I z początku sportowych wariantów miało nie być, bo po co brać wyścigowe auto, przerabiać je na drogowe, aby potem znów modyfikować do wyścigów? No kretyńskie w chuj – ale Singer naciskał. Cały team Porsche wieszczył zwycięstwo w Le Mans. Takie zwycięstwo, oczywiście wleciałoby również i na ich konto, a auto było dobre. Do kategorii GT1 wystarczał jeden egzemplarz, i ten homologacyjny nazywał się Dauer 962LM Sport. Nie różnił się się od zwykłego 962LM właściwie Nietzschem oprócz tego płaskiego spodu auta, który był narzucony przez regulaminy. Miał też aero dostosowane do Le Mans: dłuższy nos i podwójny spojler w obniżonej tylnej sekcji miały nadrabiać oddany w fazie projektowania docisk. Opony i hamulce również były większe, ale mechanicznie to było to samo auto.

GT1 miało to do siebie, że pozwalało na większą moc o dobre sto koni w porównaniu do Grupy C – a i zbiorniki paliwa mogły być bardziej pojemne. Gdy Dauer pojawił się w stawce, wielu wniosło protest. Auto nie było w zasadzie pojazdem GT1, tylko przebierańcem z Grupy C. No ale się kwalifikował. I wygrał ten wyścig. Nie tylko w swojej klasie, ale i ogólnie. Dauer był 15 sekund szybszy na okrążeniu od każdego innego uczestnika w swojej kategorii. Wielu widziało w tym wypaczenie całej idei GT1 i organizatorzy zbanowali to auto w następnym sezonie.

Dzięki swym wyczynowym genom i sportowemu doświadczeniu Porsche – a w szczególności technicznemu talentowi Singera – Dauer miażdżył wszystko w tamtym okresie. Jaguary, to on brał na lajcie jeszcze przed śniadaniem, a McLarenem do tego zakąszał. Nawet McLaren, którego wielu (całkiem z resztą niebezpodstawnie) uważa za szczyt szczytów, mógł nie wystarczać na to Porsche. Osiągi Dauera zostały zduszone dla użytku cywilnego – dodano katalizatory, przeroprojektowano linie nadwozia, aby trochę zmniejszyć docisk i opory powietrza – a i tak robił setkę w 2.5 sekundy i rozpędzał się do 400 km/h. Drogowy odpowiednik. To było najszybsze auto na drogi publiczne – dużo szybsze od McLarena.

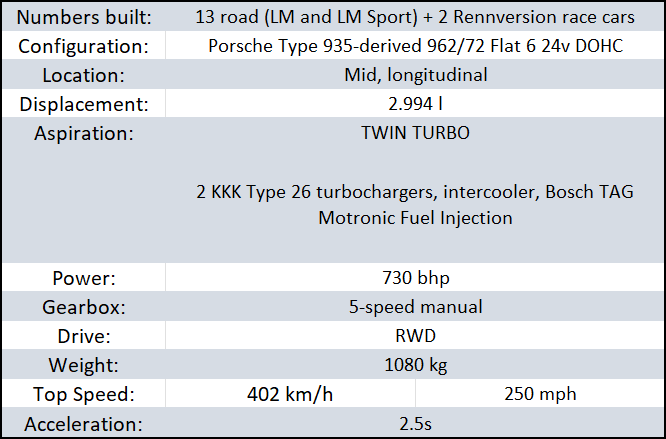

Moc czerpało z 3-litrowej jednostki Type 935 Porsche, chłodzonej wodą, na podwójnym wałku. 24-zaworowy boxer z dwiema turbinami, i po jednym intercoolerze dla każdej. Za zarządzanie pracą silnika odpowiadał system wtrysków Boscha, a współczynnik kompresji wynosił 9.0:1. Taki układ zdolny był wydać 730 koni bez VAT, czyli dobre 240 na litrze. To jest ilość, która urywa odbyt z korzeniami – i wynik lepszy nawet od techników Porsche, którzy użyli tej samej jednostki w 911 GT1 – z dużo gorszym rezultatem. Ludzie myśleli sobie “nie… to niemożliwe”. Tym bardziej, gdy Dauer twierdził, że jest szybszy od modelu F1. W listopadzie 1998 na testowym obiekcie Volkswagena, torze Ehra Lessien, Dauer wykonuje manewr, który będzie kosztował Anglików całą ich pierdoloną karierę – i przekracza prędkość 404 km/h.

Auto miało wystarczającą moc, aby zniszczyć McLarena. Cały pakiet ważył niewiele więcej jak tonę i miał idealny do tego współczynnik oporu powietrza – dużo lepszy od wyścigowych wariantów z nadmiarem docisku. Więcej jak połowę z niego zdjęto dla wykonania tego auta, przez co nie było w stanie pokonywać zakrętów na tak dużych prędkościach, ale mogło się rozpędzać do prawdziwie pojebanych wyników. Moc była przerzucana za pomocą 5-stopniowej przekładni, i trafiała na ogromnej średnicy koła. Zawieszenie, to oczywiście podwójne wahacze i sprężyny z tytanu. Amortyzatory można było regulować jak w 959. Auto się podnosiło za przestawieniem przełącznika w kabinie, i pozwalało pokonywać przeszkody na drodze – albo obniżało zapewniając dodatkową stabilność. 4-tłoczkowe hamulce Brembo zatrzymywały to cudo – tarcze o średnicy 33cm, nawiercane i wentylowane.

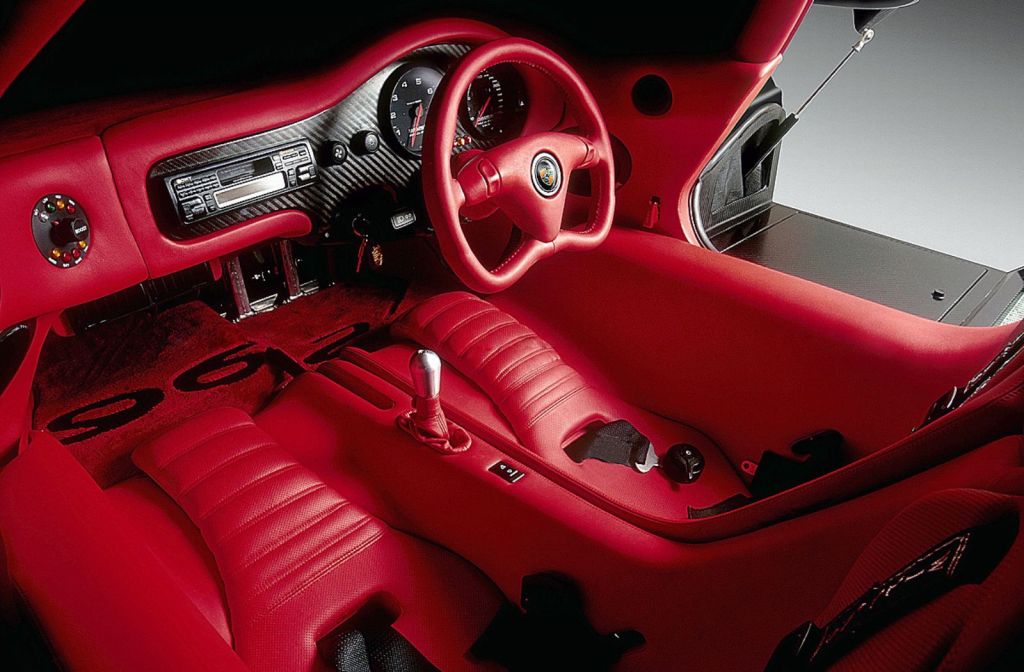

Auto prowadziło się wspaniale. Było stabilne i mimo, że sztywne zawieszenie o skróconym suwie zapewniało czysto wyścigowe wrażenia, to sprzęgło i układ kierowniczy nie chodziły tak topornie jak możnaby się tego spodziewać po torowych odpowiednikach. Nie dość, że Niemcy zainstalowali tam klimatyzację, to jeszcze taką, która naprawdę działa! Auto wyposażono w ABS, ale… jego natury nie oszukasz. Mimo wszystko, jest to jednak pojazd przeznaczony właściwie wyłącznie na niemieckie autostrady i w takim środowisku czuje się najlepiej. Na innych drogach może mieć problemy nieprzewidziane dla użytkowników tego modelu. Kabina była ciasna – wyścigowe Porsche miało tylko jeden fotel przeznaczony dla kierowcy. Dauer znalazł tam miejsce i dla pasażera, tak blisko ściśnięte, że obaj mogą smyrać się po nogach. Aby wejść do środka, kierowca musi odłączyć kierownicę, a gdy już się tam znajdzie, to może się zdarzyć, że będzie uderzał głową w szybę.

To dlatego, że siedzenie wyścigowego modelu było na środku, a w Dauerze kierowca musiał przesunąć się na bok. A kształt kabiny został niezmieniony. Dauer wolał nie ingerować w strukturę pojazdu. Jest ona otoczona ogromnymi progami, które trzeba w jakiś sposób przeskoczyć aby jakoś się do środka dostać. Progi z prawej strony skrywają niewielką przestrzeń na bagaże, ale praktyczne to to nie jest. Za tym przedziałem, jak również przy progach z lewej strony, znajdują się wiatraki jak w aucie wyścigowym. Najgorzej jednak jest z widocznością. Jedyną pomocą – choć niewielką, bo były bardzo oddalone od kierowcy – były lusterka boczne. Tylnej szyby nie było wcale. Za to do przodu kierowca widział wszystko.

Ciekawym jest fakt, że – podobnie jak z Cizetą V16T – Dauer był autem, które można było sobie kupić nowe nawet do całkiem niedawna. Nowe, nie nowe – program Cizety nigdy nie został oficjalnie zamknięty i, gdyby ktoś sobie życzył, powstałaby całkowicie nowa maszyna. Z Dauerem było jednak trochę inaczej, bo firma ciągle przyjmowała zamówienia, ale wszystkie egzemplarze 962 LM – tak pierwsze, jak i te z końca produkcji – powstały na podstawie wyścigowych modeli Porsche 962. Ciężko więc tu mówić o całkowicie nowym aucie. Dauer twierdził, że miał moc przerobową, aby wykonać nie więcej jak 50 sztuk ogólnie. Oficjalnie chyba nigdy nie podano w ile egzemplarzy tchnięto życie – są pewne estymacje – ale z pewnością jest to jeden z najrzadszych supersamochodów – a swego czasu najszybsze auto świata.

Ciekawie przebiegał żywot tego modelu. Zaczęło się od wyścigowego pojazdu Porsche, z którego zrobiono drogowy supersamochód – aby przekształcić go spowrotem w wyścigowy bolid. To Singer wykrył te kruczki w regulaminach, które pozwalały na – w efekcie wykonanie właściwie pojedynczego pojazdu i spełnienie wszystkich warunków homologacji. Organizatorzy po czasie ukrócili te manipulacje i wprowadzili wymóg 25 sztuk modelu. Dauer nigdy już nie wrócił na tor. Postawił tym sposobem “kropkę nad i” – zwieńczając karierę sportową modelu 962 tamtym zwycięstwem na torze Sarthe. Zakończyła się pewna epoka dla Porsche, bo samo 962 długo wygrywało, a przed nim 956 praktycznie tej samej konstrukcji. Dauer dla cywili powstawał aż do 2002 roku, w tempie 1-2 egzemplarzy rocznie. Ich liczbę obecnie szacuje się na ok. 13 sztuk. 6 z nich w posiadaniu Sułtana Brunei.

Krzysztof Wilk

Na podstawie: ultimatecarpage.com | autozine.org | wheelsage.org | ultimatecarpage.com | autoevolution.com | dailysportscar.com | dempseymotorsports.com | evo.co.uk | autogen.pl | goodwood.com | supercarworld.com | supercarnostalgia.com | porschecarshistory.com | supercars.net | IG: gt3point2 | joyofmachine | gt1history | raphcars | evo__master | trustfundmotorsports | apex_dreamcars | katana_ltd | deividman94 | jurassik79 | gtommy02 | abdielnfs | benymarjanac