Before starting his own company, Claudio Zampolli gained working experience in team Lamborghini. He was their research engineer and test driver for their supercar production, but a moment came to start a business of his own. From his initials pronounced – Ci Zeta – in Italian, was formed a company with amazing dreams and with backing from a legendary music producer and composer (“My name is Giovanni Giorgio, but everybody calls me… Giorgio” – get it?).

The very first example was named after its main investor and that’s why this exact one is a Moroder V16T variant (Giorgio Moroder, V configuration with 16 cylinders transversely). Later the companions split their ways and the latter models will technically be just V16T Cizetas – non-Moroders. Unfortunately Giorgio Moroder left the project before production ever started, with only one prototype built. Cizeta was a hand built car coming off the factory near Modena – in the heart of Italian supercars, and in Ferrari and Lamborghini neighborhood.

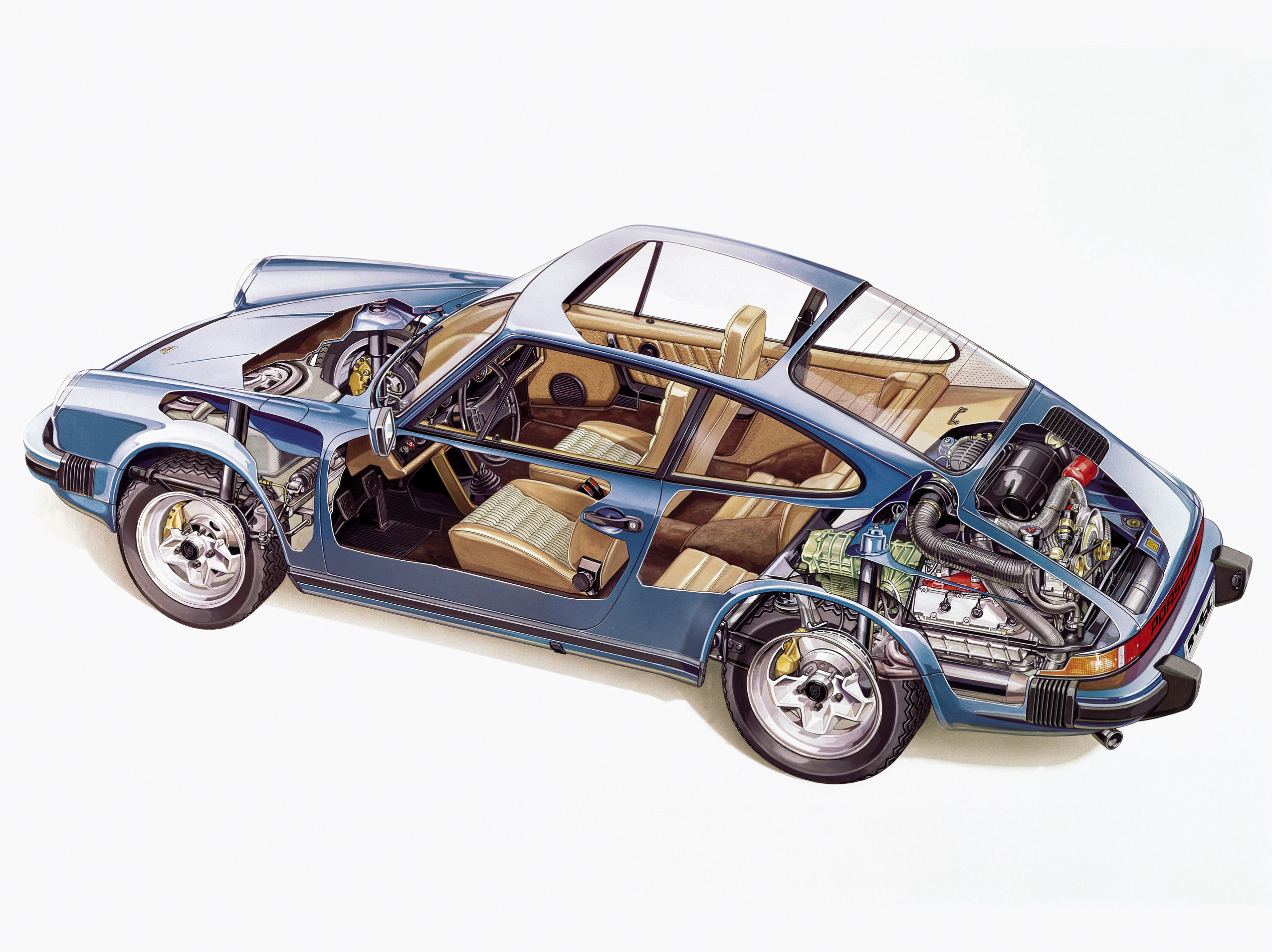

Cizeta was technologically superior to anything on the market. The golden rule of supercar design states: the car has to be low and wide – and this one was powered by, what essentially was two Lamborghini V8s joined together in one. Its a gross simplification, as the engine was bespoke, but it had Lamborghini-derived architecture. Zampolli was their engineer after all, and he likely took part in Lamborghini V8s research process. No wonder he would adapt similar solutions. Even the driveshafts with engine blocks came straight from Urraco. A high rev V16 laid transversely behind the driver, and through the 5-speed manual transmission, it sent 540 horsepower on the asphalt. It was a 64-valve motor – figure that out! It required 8 cam shafts and 2 radiators to run. And 540 BHP is much more than Diablo had. Do you understand the magnitude of this situation? You had to fit that shit under the hood, as well. One of the reasons why the car has such a sleek low profile and wide body. Never before had a 16-cylinder been put in a car transversely. Zampolli did it first.

Cizeta was standing on a very conventional tubular spaceframe and every wheel had double wishbones. The body was a work of art, and responsible was no other than Marcelo Gandini – the man behind Countach, Miura, known for Stratos, De Tomaso and later Bugatti EB110. There were no worries about his part, ok – he knew what he was doing. The car’s body was sorted. And exactly Miura/Countach platform he did use for the car. He was – in the past – supposed to introduce a project to replace the latter, but when Chrysler realized how crazy it was, they said ‘you’re drunk, go home’ to him. They didn’t even let the man fix the thing the way they wanted – they did it for him… and the Diablo came to be. Gandini then told them to go fuck themselves and he called Zampolli – Cizeta is a Diablo how it’s supposed to be! No corporate leash on the project. Untamed. The development stage engaged more people related to Mr. Ferruccio than work now in the whole Lamborghini company – now or 20 years ago. Olivero Pedrazzi was the head of the design, and the powertrain architect. Its suspension was Achille Bevini’s work, and Ianose Bronzatti took care of the chassis. All: Lamborghini. The true Lamborghini.

So complex the project was, that even though everyone working on it was top class, a legend of automobile architecture – NONE would dare to execute a running prototype. Only when Giancarlo Guerra gave green light – the first example was made. Guerra was the god of auto industry. 40 years experience on the highest level. He gave shape to the first 250 GTO Ferrari, he shown the guys at the Lamborghini how to craft their complicated Countach chassis and the bodies for it. Before the man entered Zampolli’s garage, nobody touched the thing – nobody even dared to look at it the wrong way. That’s how big this project was.

V16T was a perfect car, but sadly – unlucky. It was offered for sale at the time the supercar boom was gone, the whole market collapsed – and it never got its chance. The initial plan was to make 1 car every month, but in the end… only 9 examples were finished. They managed to craft a few more – including at least one TTJ Spider variant – after they moved to the USA. Funny thing – the car is still available. New. It was at least – till not long ago. Sure, no new cars really left the factory since 2003, but Zampolli himself – said in his 2018 interview that officially – he never closed the project and technically you could still buy a brand new ’80s supercar, coming straight from the factory in the 2020’s. At least you could, because sadly – Zampolli dies in 2021. Imagine that: a supercar from the late ’80s. Brand new. In every shape and form exceptional. A unique motor with astonishing power. No turbos, no antilock brakes, no all-wheel drive. 199mph (320 km/h) top speed and it wasn’t even tested in a wind tunnel. ‘Lamborghini never really cared for aero tests’ Zampoli said, and I believe him. It is the car that never really rivalled any other. Not per se. It paved its own path in the supercar world. And the original first example – the only with ‘Moroder’ badge – is in a great running condition, not long ago available for sale on an auction in Phoenix January 26th 2022.

Krzysztof Wilk

All sources: favcars.com | wheelsage.org | wikipedia.org | ultimatecarpage.com | autozine.org | supercars.net | caranddriver.com | silodrome.com | topgear.com