Why simple racing?

What was Rennsport Meisterschaft?

In the early 1980s, the new DTM format replaced the old Deutsche Rennsport Meisterschaft races. DRM was initially popular, but over time it grew increasingly monotonous. The format allowed cars homologated under Group 2 and Group 4 regulations, which competed in races split into two separate divisions. Division 1 was designated for models with engine displacements of 2 liters and above, while Division 2 was reserved for cars with engines under 2 liters.

In the 1977 season (roughly halfway through the format’s lifespan), cars homologated under Group 5 were allowed into the competition. These were spectacular machines to watch, but in practice, the category lacked serious rivals. This so-called Super Silhouette class featured extremely expensive, turbocharged cars with advanced aerodynamics. Not everyone had the capability to build such a car—let alone fund and maintain a racing program of that caliber. As a result, while they were crowd-pleasers, they rarely made appearances on race tracks.

The Super Silhouette era, however, was only the latter half of the DRM. The series began in 1972 as a battleground for touring cars (Group 2) and GT cars (Group 4). Division 2 provided an entry point for less experienced manufacturers, but the main attraction was Division 1, featuring large-displacement engines. The grid included cars like the Porsche 911 and Ford Capri, as well as entries from Autodelta, De Tomaso (5.8 liters), the 7.0-liter Camaro, and various BMW models.

DRM Golden Era

Although the races were primarily domestic, they were anything but dull. Generous prize money began to attract more international drivers, and teams started employing increasingly advanced strategies. As a result, the DRM evolved from a purely German championship into a prestigious international motorsport series. It was there that drivers like Hans-Joachim Stuck, Hans Heyer, and Klaus Ludwig honed their careers. DRM also played a key role in the development of legendary models like the Carrera RSR, Escort II, and BMW 3.0 CSL, while helping establish powerhouse teams such as Schnitzer, Zakspeed, and AMG.

The problem was that, in later years, naturally aspirated cars stood no real chance of fighting for victory. This applied to nearly all entries, but especially to the smaller cars in Division 2, which were completely outclassed. 1977 marked the first season under Group 5 rules. These races carried more prestige than even the World Championship at times — but often there just weren’t enough of these machines to fill the grid.

We’re talking about cars like the Porsche 935, Celica Turbo Group 5, BMW 2002 Turbo, and Escort RS 1800. All of them struggled with early development issues. The cars often broke down, and teams, short on funds, would drop out mid-season. Some of these machines only showed up once or twice the whole year. Very few could run a full campaign with one of these beasts — let alone do it successfully.

DRM – What went wrong?

The minimum number of cars required to run a race was 10 — and for Group 5, that was often a struggle. Vehicle preparation was hit-or-miss, and new models meant to replace the old ones didn’t always live up to expectations. These cars cost a fortune, yet couldn’t be relied on at all — often turning out to be a very expensive gamble. Lancia joined the fight with the Beta Montecarlo, and BMW brought in the M1, but it was Porsche that dominated with the 935, especially the K3 version.

The DRM series gradually lost its competitive edge. It became a shadow of its former self — a far cry from the wild, barely regulated Group 5 monsters of the 1970s. By the end, the grids were mostly made up of BMW teams, Ford Capris, and Porsche 935s. Porsche had no real rivals for years, and the format stopped generating excitement. Eventually, organizers decided to completely overhaul the series, shifting to a single-division format under Group C regulations. That’s when everything changed. Supercars like the Porsche 956 and Ford C100 entered the fight — and Internationale Deutsche Rennsport Meisterschaft (IDRM) was born.

There was no longer a place for touring cars in this new format. For two years, they were pushed aside to race in the Rennsport Trophäe, waiting for 1984 and the debut of what we now know as the DTM.

DTM 1984 Rounds 1-3

DTM – What exactly is that…

The new format didn’t initially carry the name we know today. For its first two seasons, the series ran as the Deutschen Produktionswagen Meisterschaft (DPM). It wasn’t until the third edition that it officially became the Deutsche Tourenwagen Meisterschaft — the German Touring Car Championship (DTM — and for simplicity, I’ll stick with that name from here on out).

DTM quickly established itself as the premier racing series in Germany. It’s worth remembering that Super Silhouette was introduced to DRM to boost excitement, but DTM ended up outshining the Group C races in no time. That just proved that touring car racing had the greater potential.

IDRM inherited the high costs of DRM, which was already a major issue from the get go. DTM, on the other hand, was much cheaper to run and take part in. The races followed Group A regulations — maybe not the most flexible in terms of modifications, but perfect for keeping costs down and lowering the entry barrier. That’s a big plus when you’re building a series from the ground up.

It also helped attract a wide range of participants. And over time, the rules could be tightened or expanded to boost the spectacle — which is exactly what happened.

… and why is it so good?

There’s no other branch of motorsport where the competition is this tight. Outside of spec series — where everyone drives the same car, like PROCAR — or American-style oval racing like NASCAR, DTM really stands out. It’s hard to pick consistent favorites, because even older, well-sorted machines can hold their own.

In any given race, there might be 15 drivers realistically fighting for the win. Sometimes, a 2- or 3-year-old car can still take on the latest machines and end up at the top of the season standings. In its very first year, drivers behind the wheel of seven different car models fought till very late phase of the season with everyone holding good chance for the title.

DTM rounds quickly went from being warm-ups before Formula 3 weekends to becoming the main event. It earned the nickname: “Formula 1 of touring cars.”

The format turned out to be a perfect hit, as it allowed organizers to keep the racing extremely competitive. Cars were regulated in terms of minimum weight and tire width. A ballast system was introduced — dominant vehicles could receive up to 120 kg of extra weight, while engines with three or more valves per cylinder started off with a 70 kg penalty. Meanwhile, underperforming teams were allowed to lighten their cars, which encouraged less experienced drivers to join the grid.

As a result, a single race could see up to 40 cars on the starting grid, with championship points awarded to the top 18 drivers. Many teams entered the competition completely from scratch. Not all drivers were professionals, and the field featured cars based on 16 different production models — a level of variety unmatched anywhere else. Opels and BMWs alone could be seen in at least three different variants during a single race.

Round 1 – Zolder – Have you been to the opening?

Zolder – what is it?

The season kicked off on March 11 with a race at the Zolder circuit. Over 3,000 spectators turned out to watch the action. The race consisted of 24 laps on the 4.3 km track, totaling roughly 102 kilometers at an average speed of 125 km/h. Drivers behind the wheels of Rovers and BMWs were considered the favorites going into the event.

The Belgian circuit hosted the season opener in March, and conditions were brutal — drivers had to brace for both rain and snow. The weather caught many off guard, with some cars proving unfit for competition altogether. A few entrants were even excluded by the organizers; for example, Alfa Romeo teams had to replace their exhaust systems just to meet the decibel limits. In the end, 24 drivers lined up on the grid, and 18 made it to the finish — meaning every finisher walked away with points.

24 cars on the grid was a strong showing — especially considering this was an entirely new racing series. The most common sight? BMWs. German teams had already been running the E24 635 CSi in the ETCC, and the proven platform seemed like the perfect fit for the national championship.

But BMW wasn’t alone. It now had proper rivals in the form of the Rover SD1 and American Muscle like the Ford Mustang and Chevrolet Camaro. Alfa Romeo showed up too, but — like a few other smaller contenders — just didn’t have the cylinder count or engine capacity to properly challenge the Bavarians.

Belgium Race

Rover had a V8 under the hood, and both Jörg van Ommen and Olaf Manthey secured strong qualifying spots – first and third on the grid. Splitting them was Hans-Joachim Stuck in a BMW, who dominated most of the race from the start. But just two laps before the finish, disaster struck: he lost a wheel. That opened the door for Grohs, who swept past and cruised to victory with nearly a 30-second lead.

Rover’s troubles kicked in early – likely due to poorly chosen tires. They wore out too quickly, but with that unpredictable weather, it was a total gamble. Some teams hand-cut treads into slicks, others gambled on full rain tires. It was chaos. Meanwhile, Alfa took a serious power hit from their hastily zip-tied exhaust replacements. As for Rover, they also struggled with power in this first round and couldn’t crack the top five. BMW swept the podium with Grohs, Schneider, and Strycek taking the honors.

Round 2 – Hockenheim – And the winner is…

Hockenheimring Baden-Württemberg

April 8 brought the Jim Clark Rennen – a DTM round held at the Hockenheim Motodrom. Compared to the Belgian opener, this was a much faster and longer circuit. At the time, it stretched 6.8 km per lap, with average speeds around 157 km/h. Drivers had to complete 15 laps, which again meant just over 100 kilometers at serious pace. It was also the first real opportunity for the Foxbody Mustang to bare its teeth.

How did it go?

In the April race, 33 drivers lined up at the start, and the action was way more intense than in Belgium. Van Ommen once again secured pole position, with Olaf Manthey lining up beside him in the second Rover. Grohs, piloting the E24 BMW, started just behind them. Early on, five drivers broke away from the pack while further back, Jürgen Fritsche struggled with brake issues – his Kadett GT/E clipped two other cars entering the chicane and didn’t finish the race. The Foxbody showed promise with the fastest sector times but ended up heading home early too, plagued by both ignition problems and tire trouble. Just brutal luck.

Despite the best efforts of the Rover SD1 drivers, it was Grohs in the BMW who crossed the finish line first. Behind him came Volker Strycek in another BMW 635 CSi, followed by Peter Oberndorfer in the Alfa Romeo GTV/6. But the drama didn’t end there – Grohs’ CSi was found to have illegal valve lift on at least two cylinders, leading to his disqualification!

What made it especially controversial was that the engine came straight from the factory – identical to what other BMW drivers were using. Still, only Grohs’ result was scrapped; the rest of the standings were left untouched. As a result, no one was moved up to claim victory. The race officially ended with a second and third place… but no winner. Fans saw 23 cars cross the finish line – and not a single one take the win.

Runda 3 – Avus – Buy one get one free

Autobahn racing? Shut up and take my money!

Berlin, May 13. Five thousand spectators followed the action as 27 crews lined up for the third round of the DTM, run over two heats. One lap was a long sprint covering 8.1 km. The Automobil-Verkehrs- und Übungs-Straße was, in essence, a historic racetrack (in the sense that it’s no longer in use), built along a stretch of highway running through Berlin. It consisted of two long straights ending in loops. Straight, hairpin, straight, hairpin – and that was it.

A very distinctive track. It was built in 1921, and back then the full layout was nearly 20 kilometers long. I mean… that’s a really long straight. After the war, it was shortened to around 8 km, but it still remained one of the fastest circuits out there, with average race speeds hitting 180 km/h. Naturally, in a race like this, everyone bets on the big American muscle cars with massive engines. BMWs and Rovers have to play catch-up, while the Alfa Romeos and Kadetts can only really hope to grab a few points at the back of the grid.

Race results

27 cars lined up for the event, but the race format was a bit different this time – two heats of 7 laps each, with half-points awarded per race. Van Ommen started from the pole for the third time in a row and fought hard right up until the final lap, where a late braking move cost him dearly. He damaged his Rover, smashing the oil pan and steering rack – though he still managed to finish second. Unfortunately, the car wasn’t fit for the second race.

The Mustang, with its 5-liter V8, was right at home on this fast and wide circuit. Manfred Trint made perfect use of that power and dominated the first heat, finishing more than 4 seconds ahead of anyone else. Third place went to another muscle car — a 5.7-liter Chevrolet Camaro Z28. Driver Peter John had started way down the grid but climbed his way to the podium through consistent, smart driving.

The second heat was even more dramatic. Trint’s Mustang took the lead early, but then blew out both front tires and had to limp back. That opened the door for six drivers to battle it out for the win. The brakes on the Camaro gave out completely – and it slammed straight into Grohs’ BMW, ending the race for both of them.

That left four cars fighting it out to the line – and they finished practically on top of each other, with less than a second separating first from fourth. The Rover finally earned its moment, picking up half-points for the win. Von Bayern and Strycek followed close behind in their BMWs.

Epilogue – BMW and Rovers: old but still fierce

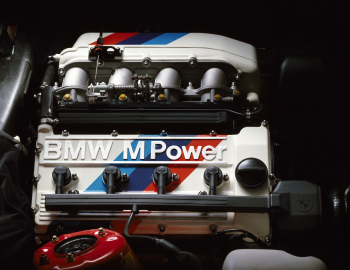

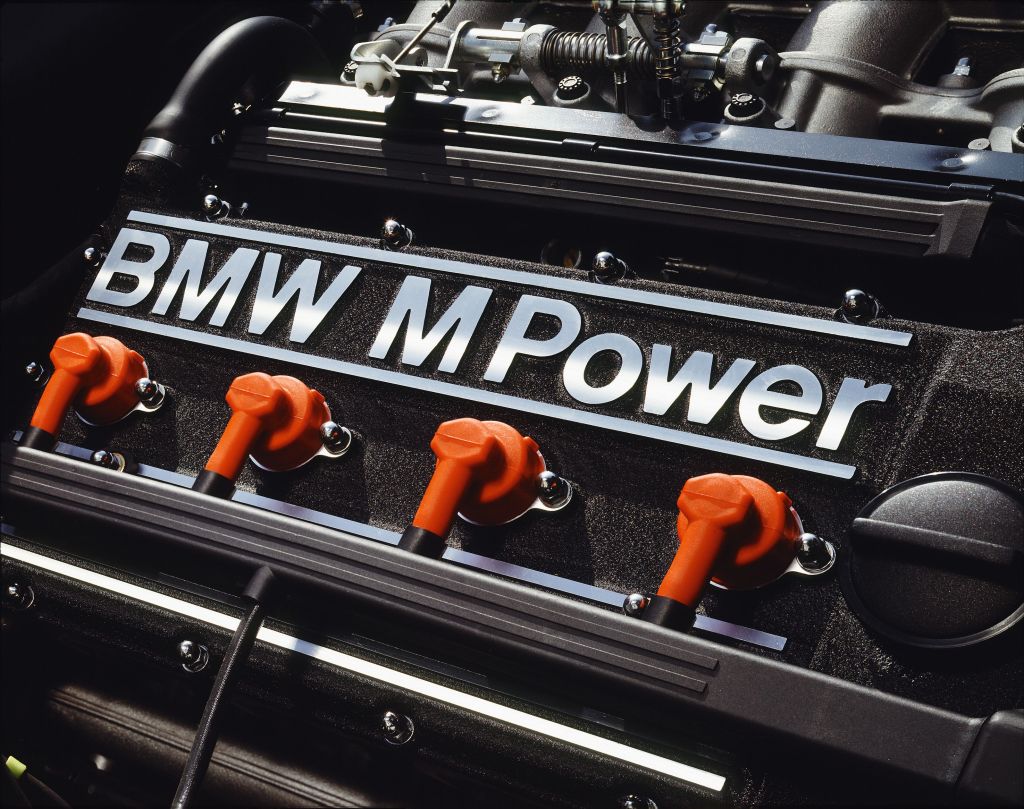

BMW E24 635 CSi

The new DTM series (then called DPM) was packed with adrenaline right from the start. The first race didn’t go exactly as everyone hoped, but each following event brought more excitement and variety. It quickly became clear that to win, you needed at least 3 liters of engine capacity. Rovers and BMW CSi ruled the field with their 3.5-liter engines – whether inline sixes or V8s – no matter the configuration.

Despite the presence of newer models, the BMW 635 CSi was one of the best cars of the 1980s and enjoyed the greatest trust from drivers. It’s no surprise – this car produced nearly 300 horsepower, was lighter than its American competitors, and despite its considerable size, it proved itself three times over in European ETCC races. And in the DTM, it had to carry extra ballast! Yet, full factory support and a refined design gave it the edge it needed.

Rover SD1 (3500/Vitesse)

The Rover Vitesse also got off to a strong start. Van Ommen may not have won, but he started at the front in three races. Like the BMW drivers, he relied on a proven design. The Rover Vitesse had the same advantage in engine displacement and similar power output. In fact, both models competed directly against each other in the same market segment.

Rover, however, had a serious ace up its sleeve – one that, if used right, could really shake things up. On paper, the car seems too big and heavy to be a serious race contender. The thing is, the SD1 model is a perfect mix of simplicity and modernity, and the Vitesse variant holds huge potential. These cars still run with a solid rear axle, but their V8 engines featured fuel injection, which meant drivers of these models would continue to show strong performances for quite a while. You just wait.

The early rounds of the Deutsche Tourenwagen Meisterschaft already gave us a taste of what these cars and their drivers were capable of. After three races, the overall standings looked like this:

| Points | Driver | Car |

|---|---|---|

| 42 | Volker Strycek | BMW 635 CSi |

| 24 | Leopold von Bayern | BMW 635 CSi |

| 22 | Jörg van Ommen | Rover Vitesse |

| 20 | Harald Grohs | BMW 635 CSi |

| 18 | Udo Schneider | BMW 635 CSi |

Krzysiek Wilk

— — —

Credit to all the sources used in creation of this text:

T Voight – DTM: The Story – the official DTM book | M Buckley – The Complete Illustrated Encyclopedia of Classic Cars | D Lillywhite – The Encyclopedia of Classic Cars | The Kingfisher Motorsports Encyclopedia | R Nicholls – Supercars | ultimatecarpage.com | touringcarracing.net | wheelsage.org | wikipedia.org | autozine.org | carandclassic.com | supercars.net | silodrome.com | autonatives.de | FB: EasternBMW | snaplap.net | YT: KhS Ralf Schmitz | netzwerkeins.com | racingcircuits.info

and likely I forgot about someone as well…